Charles Nodrum Gallery

May 25 – June 15 2024

The colour blue has a long and profound history in art: lapis lazuli of ancient Egypt, ultramarine of the Renaissance, cobalt from China, indigo from the Americas, they have been amongst the most prized pigments in history. Equally significant are the associations: the heavens, the Virgin Mary, French Royalty. In popular culture too, blue looms large: “the blues”, “once in a blue moon”.

So “Why blue” seems the obvious question to ask about this exhibition. Asher Bilu’s first response is equally obvious: “Why not?” It’s not his favourite colour, he says, and indeed he has a long history of never shying away from any colour or finish bright or wild.

The blue moon of 2019 was a moment of moon fever that Bilu got caught up in, and many works in this exhibition date from that year. Indeed, 2019 was the year he felt compelled to change the colour of Finite Chips,1988-2024 previously white, to the blue you see here. All of the blue in Bilu’s work is made from raw pigment. All raw pigments have a natural glow, says Bilu, but blue in particular has a mystical quality to it too.

Musicality in the sphere of thought (Einstein), 2021, is arguably the centrepiece of this exhibition: an installation comprising a blue coloured cello balanced on a mound of pure ultramarine pigment, on a glossy black stage set before a wall of 24 carat gold leaf. Bilu talks about his work in general coming from the computer in his brain: a mysterious network of things collected and observed which produces ideas. In other words, his subconscious. This particular work comes from a less mysterious but no less fundamental source. Bilu studied violin from the age of 7 and music has remained profoundly important to him. Years ago, he was given a cello. It was broken, with no strings, and it sat in Bilu’s studio for years gathering dust while he stared at it – a beautiful piece of sculpture in and of itself – and the idea of how to use it gradually came to him. He took the cello to a restorer who restrung it, and then Bilu painted it blue and arranged it for this installation. “This piece represents how I feel about music”, he says, “the gold is the notes, the sound.” Bilu talks of Einstein claiming music was hugely important to him too (Einstein also played the violin), and the illusion of the cello floating on its bed of pigment symbolises for Bilu the way music relates to physical laws and the way music, creativity and science all share a kind of magic – and are hence beyond description. “In painting”, he says, “I don’t use conventional materials or means but my approach is classical.”

Today, Bilu plays the Stroviol, also a string instrument, invented by Johannes Stroh, a German electrical engineer at the turn of the last century. He plays every day, improvising, for hours. “Music has volumes,” he says, “textures – all sorts of aspects that you can relate to paintings. It’s abstract, but in my mind it’s the same. When I paint it’s as if I play music and when I play music it’s as if I’m painting – the same feeling. They go hand in hand. Dubuffet was always playing music, Karl Schwitters was famous for his concrete music recordings – just his own voice. Other artists made their own instruments in order to create something new, to create a sound or a form of expression that was different or original.”

Kate Nodrum, 2024

A few words from Charles:

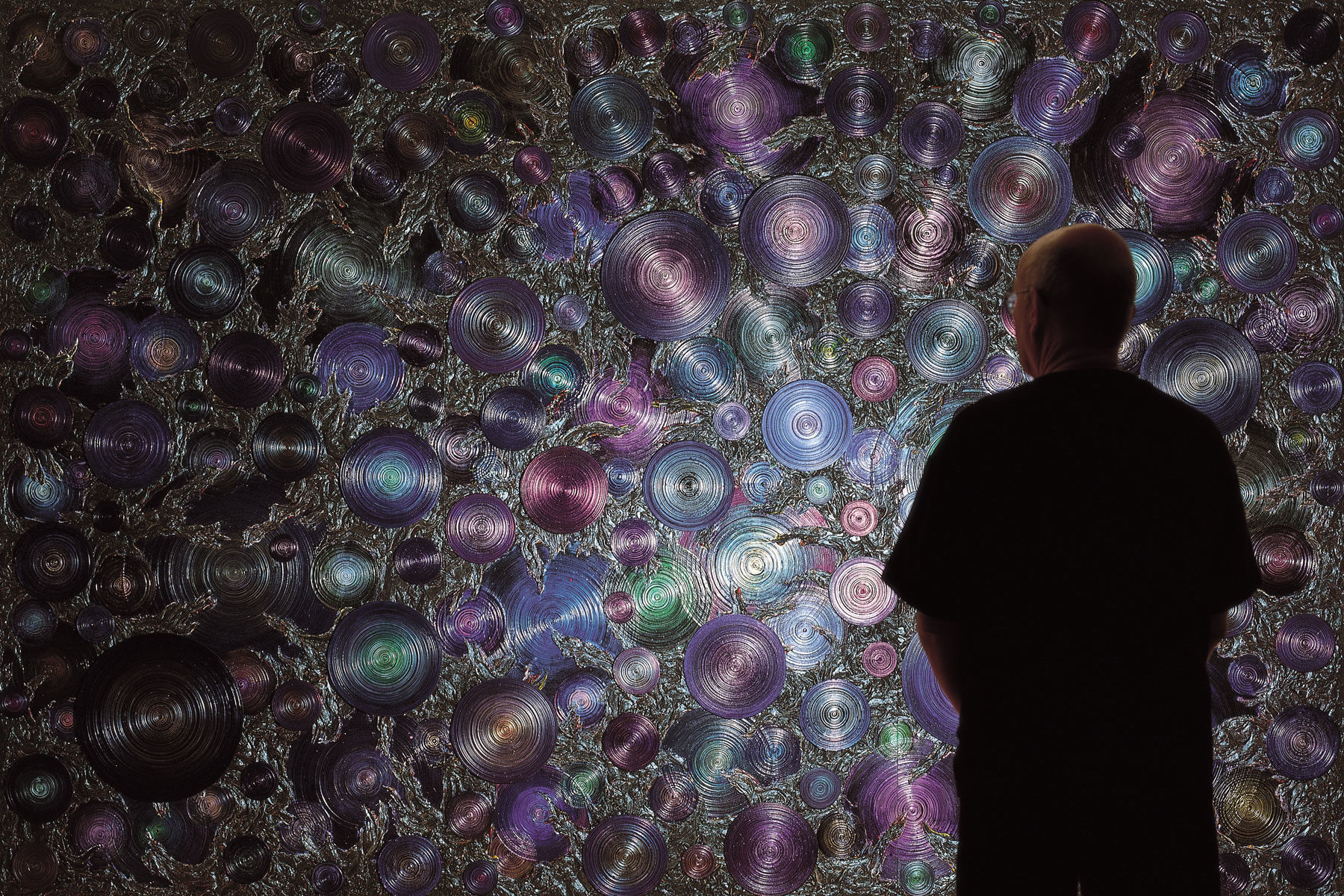

When I first met Asher in the 1970s I had just started working for Joseph Brown and I quickly took to his work, particularly the black paintings – the graphite series – with their smooth, almost shiny, central circle resting within a heavily textured square, as rough as a bitumen road. There was a numinous element that I could sense behind the challenging black square whose very physicality seemed to defy any access. I still have the graphite series painting I bought back then, and it still holds both its iconic quality and its symbolic presence – even though I still can’t see that it symbolises. Bilu’s recent work is of a scale that dwarfs the work of the past, but retains the enigma.

Charles Nodrum, 2024