15 March 1969

Asher Bilu’s life was practically ruled by music and the violin before he joined the Israeli army and fought in the Suez affair. Even there, what he remembers most, running across open fields under enemy fire, was the strangely beautiful music the bullets made as they flipped past.

He was brought up on a kibbutz outside Tel Aviv.

He didn’t conform too well to communal life where individual ambition was not encouraged: when other boys received medals and belts of approval, like scout badges, he got away by himself and improvised for hours on the violin which he thought was to be his career.

He came only imperceptibly to painting.

“In the kibbutz my biggest influence was for a time an art teacher – a distinguished painter – we almost shared studios. I learned a lot from the way he evolved. It fascinated me. We always talked a great deal and I always showed him what I was doing.

“Without even thinking, I was always involved in painting – it was one of my major interests – but I never thought about it, it just seemed to happen.

“By the time I left the army I had started to paint full time. I formed a studio and painted for almost a year and then came to Australia.”

Asher Bilu came to Melbourne from Israel in 1956. He didn’t know anybody and it was six months before he walked into the Museum of Modern Art with some paintings under his arm and was given his first showing with the Contemporary Art Society.

Since then he has held several exhibitions – in Melbourne, London, Holland – and now there is one in Sydney at the Clune Galleries.

“I still have a deep interest in music and practise every day. I couldn’t separate myself from sounds. It’s all part of me. It all came out – this involvement with sound and image – in my Sculptron.”

The Sculptron was a strange and wonderful object he made a couple of years ago out of steel and electric impulses. You stood in front of it and every sound you made, every whisper was translated into vibrating images.

“The idea was that it would transform sounds into images, but also it had its own sounds, its own images. It’s no different from paint, but it’s so much more real.

“I hope to continue in this medium because it provides something like a total environment.

“I realized that when I found out about painting, one of my prime concerns was the magic of light, light in the mystical sense, illumination.

“Somehow I found myself attracted to the electronic medium. I feel it will open up infinite possibilities of expression. Electronics is a relatively new thing yet it is a medium like oil paint or watercolours – just a medium – a laser today is not at all unique to me.

“In ten years’ time it will be just as common as a light bulb with no special artistic value. It should be possible to make paintings or objects, say, from four lasers meeting in the middle of a room.”

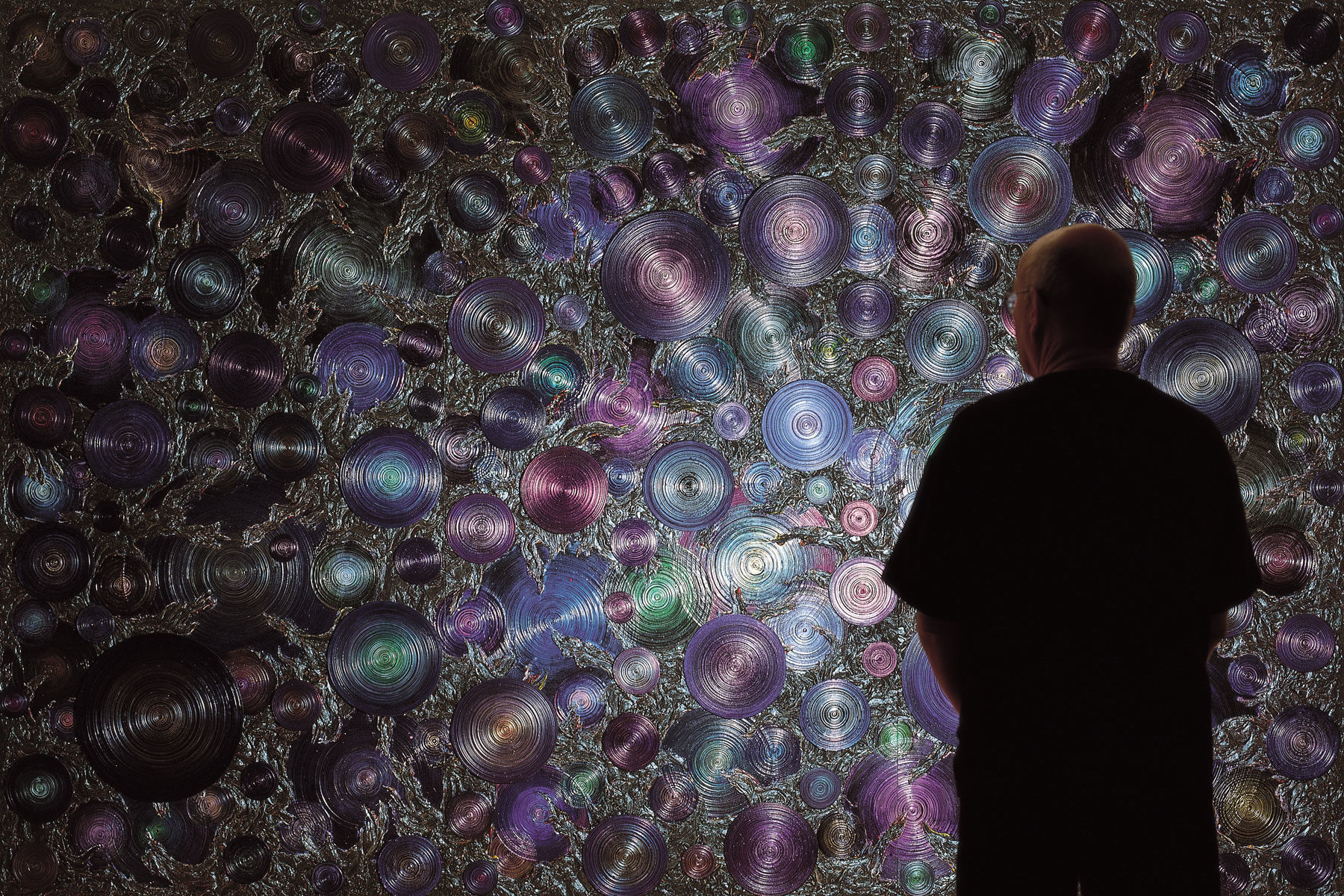

The present exhibition is not of electronic devises but of paintings, some of them begun three or four years ago and worked on since.

He like to live with his paintings for a long time before showing them; to select, to improve, to polish.

They nearly all begin, like his improvisations on the sarod – a plucking instrument invented by the Persians and improved by classical Indian musicians – as very simple themes, slowly and elaborately developed.

He uses a quick-drying glue, mixed with caseins, enamels, oils, which sets almost instantaneously and allows him to work over the first spontaneous gestures.

“I started off with the conventional techniques, painting with beeswax and pigments, but found that I wasn’t satisfied with them and then discovered this glue. As far as I know I’m the only one in the world using this particular medium.

“I found that it repelled water and would respond to fire and heat and so create textures which had not been used before.

“I throw the shape – almost as a potter would – like Klee making a line and seeing where it would wander.

“And actually many of the smaller shapes which people have taken for sperm, or tadpoles, or ornamental petals, really are just perfectly natural forms produced by squeezing tubes of glue: particles in place …

“In a sense my paintings are influenced by eastern mythologies. I find that their conception of time is very similar to the way I think and feel. They’re really not about anything specific, but about the feelings of time, creation, beauty, with which I find an affinity.

“I start with a very simple form, like a simple melody, and develop it, create it – let the feeling, the mood, the whole rather than plan a picture.

“That’s why I’m so opposed to those hard-edge paintings which are planned and calculated and never give one the feeling of either spontaneity or discovery.

“I make sound, like painting, with no rules.

“People can identify it with almost anything they know, but the cannot pinpoint it and say: this is what it is.

“You see, Paul Klee was incredible because he always remained so pure. Though he’d been into everything, his work was never affected by, say, research into the nature of creation – there were no rules – he felt from the start that the whole thing was a mystery, even to him, despite all the rules he himself made.

“I would like to think that my paintings are mystical – they are not abstract – they use abstraction as a language but are always very, very real, but saying something beyond the limitations of the real.

“They may have references to mythology, to sayings like ‘wisdom is something that comes through a dark door’ or ‘there is darkness within darkness within darkness’, or to Hindu ideas of time and beauty, always trying to discover, to perfect our language no matter what medium we are using.

“I feel too in myself – it’s something I feel very strongly – the combination of east and west. Being a member of a Semitic race, it’s something I find in me.

“When I play music, the Eastern sounds are familiar to me without effort; and the Western culture, the Western idea, that too is somehow merging in me.

“I don’t believe in any particular school. I’m always influenced by other painters and paintings but I wouldn’t classify myself with any.

“I see these movements come and go, but I’ve always developed with my own ideas, progressed as I’m working.”