It is difficult to explain how or why one becomes an artist. We are all born with an urge to express ourselves, but few of us make artistic expression a way of life. Perhaps this way of life is somehow chosen for us by forces beyond our own volition.

My father chose the violin for me. At an early age, music became my first involvement with art. At first I rebelled against the discipline required to master the instrument, but when I understood that there were no short cuts to obtaining the technique required to allow self-expression, the hard work became not only acceptable but a necessary part of my life.

At the age of 14 I was sent to live on a kibbutz away from the city, and my life changed completely. I had always loved nature and to live within it was a treat that I fully utilized. However kibbutz life demanded a group spirit, and discouraged personal interests and ambitions. My violin had come with me, and before long I realized that it had became my guardian. Playing music was important to me, but I did not know at the time how much I needed it in order to protect my individuality. The more my commitment to music was questioned the more dedicated I became, to the point where I was ostracized by most of the other members of the kibbutz. I suffered the pain of an outcast.

Once, during a crisis, feeling very much alone, angry and needing to cry, I picked up the violin and played. When I stopped, I realized that a miracle had occurred. I had not played Bach or Mozart, I had played ME; I had improvised, and it made me feel strong and fulfilled.

It was during that time that I started to draw and paint. Our school painting teacher was an artist who had a studio on the kibbutz. To me his studio was a temple. Everything I loved seemed to be there. I loved the smell of the paints, the tools, the brushes, the books, and watching him paint was indeed a privilege. I became more involved with painting, but did not consider it a serious alternative to music.

During my army service I was forced to abandon my violin, something only the army could have made me do. I automatically turned to drawing, and wherever we were, I pulled out a pad and drew whatever I could see. I experienced a new sense of freedom, and came to accept that as a painter I was able to express feelings and ideas that I could not so easily do with music.

By the time I left the army, I had made a personal and absolute commitment to becoming an artist. At no point did I consider attending an art school because any school seemed to me to be synonymous with restriction of originality. I visited museums and galleries regularly, looked at books and magazines and whatever was available, but above all, I started to paint, and soon after moved to live in Australia.

In those early years I painted more with my heart than with my eyes. I remember as a young painter coming across the writing and paintings of Paul Klee. His approach to art and life was magic to me, especially the variety of media that he applied in his work. It was a kind of alchemy that I was waiting for and felt very comfortable with. For a while I could see his influence in my paintings growing stronger and stronger, and I feared becoming a captive to someone else’s idea, but with each new painting my voice became more confident and my pictures entirely my own.

As my involvement with painting grew, so music returned to my life. The violin through which I had discovered improvisation was ultimately replaced by the sarod, and making music became a part of painting. I hear music when I paint, and see paintings when I play music.

I have chosen to deal with abstraction because for me it provides the freedom to explore the unknown. To paint figuratively is to paint what I already know or have seen before. The language of abstraction is universal (as is the language of music) and can be accessible to anyone who takes the time to see. I want to use this language to express the beauty and the mysteries of our existence in an infinite universe of which we are only a small part. I hope my optimism and love of life will be contagious.

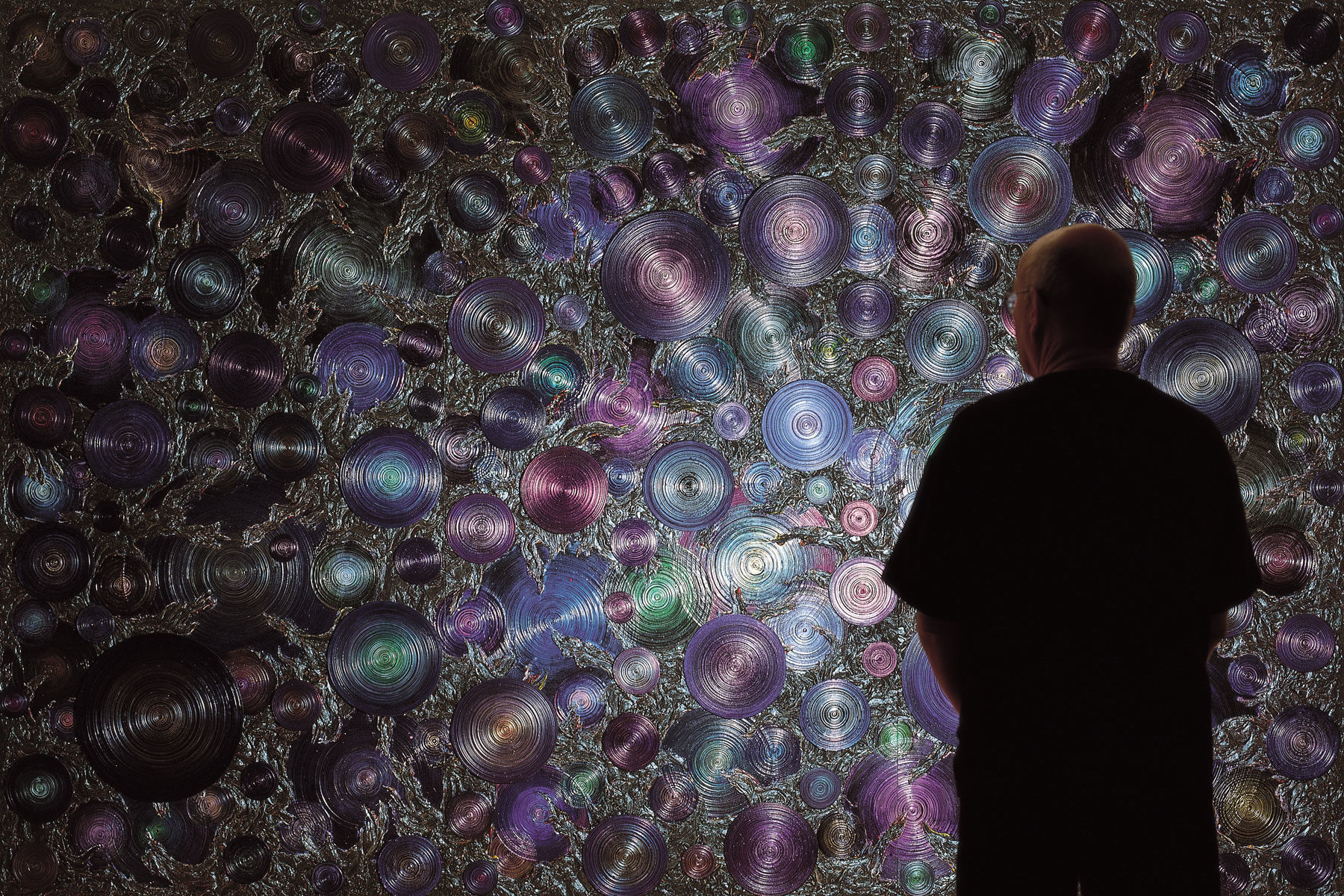

Until the seventies I had been working on textured paintings, using various conventional and unconventional materials. The physicality of the painting was always important to me, and I formed the paintings by using various methods – fire, water, different tools etc. Experimenting constantly became a natural thing for me, and paved the way to my current work.

As my paintings became more and more dimensional in effect, I began to feel the need to break away from the two-dimensional surface. Nothing is Lost is a pivotal work since the build-up of paint on the surface suggested to me the possibility of extending the paint into three-dimensional space.

The first painting in the new style was Zone 1 This painting retained the textural feel of previous work but the cut- out sections of the painting extending into space proved to be an exciting and successful discovery. Without any hesitation, I proceeded with bigger works, like Zone 2 still using textured surfaces and just minimal but effective cuts.

There were more discoveries in the process. As I cut the paintings, I found that they could be used as stencils for the creation of new paintings; by moving the stencils on a board and spraying each take with a different colour I could create an X- Ray like effect, a computer-like build up of images, and again one or two simple cuts almost seemed inevitable. Works on paper followed and then much larger and more complex works which utilized a variety of media (The Dream).

All along I have done the odd work on a flat surface, but always with a strong dimensional effect (The Journey)

The early dimensional paintings were formed with plywood, then cut out and mounted on wooden blocks, set on a variety of levels.

The recent paintings are of a different nature altogether; indeed the paintings are dimensional, but the materials and the approach completely different. Here the paint dictates almost everything. The paint is applied on non-porous sheets, then peeled off and mounted layer upon layer to form the complete painting. No blocks are used ; the paint supports itself.

The paint (a poly-vinyl alcohol resin) is a rich glossy enamel- like medium. It was not similar to anything I had worked with previously, and it took ten years of experimentation before I could utilize all its properties. I was inspired by the memory of a huge reclining Buddah I had once seen in Ceylon. He was painted in rich bright yellow enamel, gleaming with light, so simple and effective. It encouraged me to go on.

Because the paint is self-supporting, I could use it as a sculptural medium, creating works that were “sculptures made of paint”. The first of these was Amaze , a walk-through painting 42 metres long and 3 metres high and which used 1 tonne of paint. It was by creating Amaze that I discovered all the paint could do, and this led me to make other works in the same vein (Googol 1 and Googol 2).

My intention with the recent works was to make them in the conventional format of the frame, so that they could be interpreted as paintings, although it is obvious that their three-dimensional quality blurs the distinction between painting and sculpture. Call it sculpture, or call it painting, my aim is to create visual ecstasies.

The possibilities seem endless.

Asher Bilu, 1988.