Making Paintings Sing?

‘Those people who look at an abstract painting and can’t quite relate to it will listen to a piece of music and love it and get a lot of pleasure out of it. Some of them will say they even understand it. Yet it is completely abstract and yet is speaks to you, so in that sense abstraction works for me, and what I try to do with abstraction is to breathe life into it – to make it sing.’

‘I always find the analogy with music interesting.’

Asher Bilu on the ABC Arts Show (Sept 2000)

Asher’s musical take on painting is compelling. As a musician myself, with no expertise at all in painting, or, for that matter, in writing about art, it’s a good entry point for me into this world. Though from the onset it should also be acknowledged that music is only one of many eclectic and fluid influences into his creativity. There is no desire here to unduly emphasise its influence on Asher’s painting at the expense of others, or to distort its role in his creative process. It must be said that Asher reads widely, and has a particular passion for cosmology, astronomy and physics. As he says himself ‘I have always had a fascination with science as a source of inspiration’.* Outside of an engagement with this rationally based knowledge, other interests such as the art and aesthetics of diverse cultural traditions, cooking, yoga and gardening, to name just a few, contribute to an overall sense of wonderment with the world and endow a quality of richness that can be only appreciated and admired.

Nevertheless, music has also long been a part of Asher’s life. As a child growing up in Israel, he received training in classical violin, nurturing his life long love and knowledge of western classical music. Asher constantly listens to music while in the studio. Not just as soft background music, that would be far too opaque an experience. Rather the generous volume that positively charges out of the speakers somehow ensures that the sound vibrations become mixed with the paint itself. A genuine and deep appreciation of many genres and styles of music from home and around the world inhabit this soundscape. But overwhelmingly, the music of choice for Asher is Hindustani music – the classical music of North India. We are not just talking here about a passing familiarity with a few commercially released recordings. Rather, the collection amounts to many thousands of hours of the best and rarest recordings over a number of decades sourced from preeminent archives and private collections all over India.

Asher also took up playing the sarode (a Hindustani plucked string instrument) some forty years ago and over a number of years received lessons from the well known maestro Pandit Ashok Roy. Asher’s journey into Hindustani music has found him in the company of many of the top line Hindustani musicians in India, facilitated by extensive travelling in that country over the years. At home, Asher and his wife Luba have hosted a number of Hindustani concerts in his studio over the years. So it’s fair to say that the engagement with Hindustani music is a little bit more than a passing fascination for him.

It’s not surprising that analogies between painting and music are invoked and resonate here. While it may be possible to indirectly discern or sense connections between painting and musical performance, the bitter paradox is that such connections are also elusive and readily resist articulation. This is hardly surprising given the indeterminate bevy of conscious and unconscious thoughts, emotions and physical elements that are harnessed together in the creative act to generate a coherent creative flow. It would be somewhat disingenuous to attempt to reduce any connections between painting and music to a simple set of glib equations. Despite the glaring obviousness of the sea of difference and dissimilarity that distinguish these two very different art forms, nevertheless convergences and similarities can also be discerned in the artistic goals and outcomes of the two.

Asher’s take on how the two might be connected is, ‘[my painting] … looks like what you imagine sound to be as it echoes away’. In the aesthetic sensibility of Hindustani music, it is in the fading of the sound, the lingering of its resonance, that magic resides. The emotional impact of the music is heightened through the mindful crafting of delicate nuances of articulation and inflection of the sound which adhere to, and inhabit, the reverberation and resonance of musical sound. It is one of the many subtle characteristics that pervades the intellectually complex and emotional powerful melodic system of Hindustani music. This property is certainly not unique to Hindustani music, and is also treasured and described in many forms of music where it is known by different names: the mojo of Blues, the duende of Flamenco, the saltanah of Arabic music and so on. For some, it reaches its pinnacle in the performance of a raga, the quintessential musical entity of Indian music. On the face of it, a raga is an abstracted melodic seed that a performer nurtures and develops through improvisation into a coherent aesthetic experience, in the same way that a chef may transform the few words of a recipe written down somewhere into a sublime culinary experience for the senses.

The way Asher’s expresses his own approach to abstraction, ‘abstraction to me is a challenge, it is my song’, especially lends itself to a comparison with the artistic goals of the introductory alap section of a raga performance. In alap, the fundamental elements of music are explored through, and charged with, the conscious and deliberate abstraction of musical sound and time. While there is a subtle yet shifting shape and form that frames the limits and guides the movements of such an exploration, the primary artistic goal at play is to invoke and communicate an emotional and intellectual intensity through its performance. Abstraction is key to this process as it provides the artist with the best canvas to achieve an aesthetic potency.

Further, the alap provides an artistic mind with the opportunity to explore fundamental creative elements in ever increasing levels of complexity and virtuosity through the immediacy of improvisation. In the sense of it being an open-ended artistic arena, the alap is musical abstraction at play in dialogue with a deep and subtle structure and form with the goal of creating emotional intensity.

What is important here is the aesthetic effect, which is achieved through the careful construction of emotional states or flavours. It is this goal that underscores the sophisticated rasa system, an aesthetic philosophy that pervades and informs creative practice in India. In the end, it is the emotional effect (rasa) by which the aesthetic success of the work is conventionally understood. The challenge for artists is in continually generating, maintaining and refining this emotional effect; bending it their way and making it their own ‘song’. It is perhaps no coincidence then that the same word, yantra (lit. device), is used in Sanskrit to denote both a musical instrument and a visual diagram. The logic being that they are just both devices used to achieve a goal.

It is in this loose sense that artistic goals and aesthetic effects of the raga alap are not unfamiliar in many of Asher’s works. This is not to say that Asher’s approach to painting can be explicitly compared to the structure and performance of Hindustani music. This is clearly not the case. Rather the two explore parallel if not similar artistic territories despite them inhabiting two different media, two different cultural traditions and appealing to two different senses. But importantly they do share a parallel and sublime quest for invoking, through abstraction, a compelling sense of immediacy and heightened emotional effect.

The immediacy of abstraction in music is further intensified through the spontaneity of improvisation. The act of improvisation is often understood as playing with the idiom. The ability to do so successfully is derived from such a familiarity and command over the idiom that the artist can spontaneously experiment and reinterpret the elements at hand into a seamless coherent outpouring. ‘Experimentation was always a part of me’. Experimentation in this context, is improvisation by another name. Asher is a born improviser, not just in music, but cooking or any other creative medium that he turns his hand to.

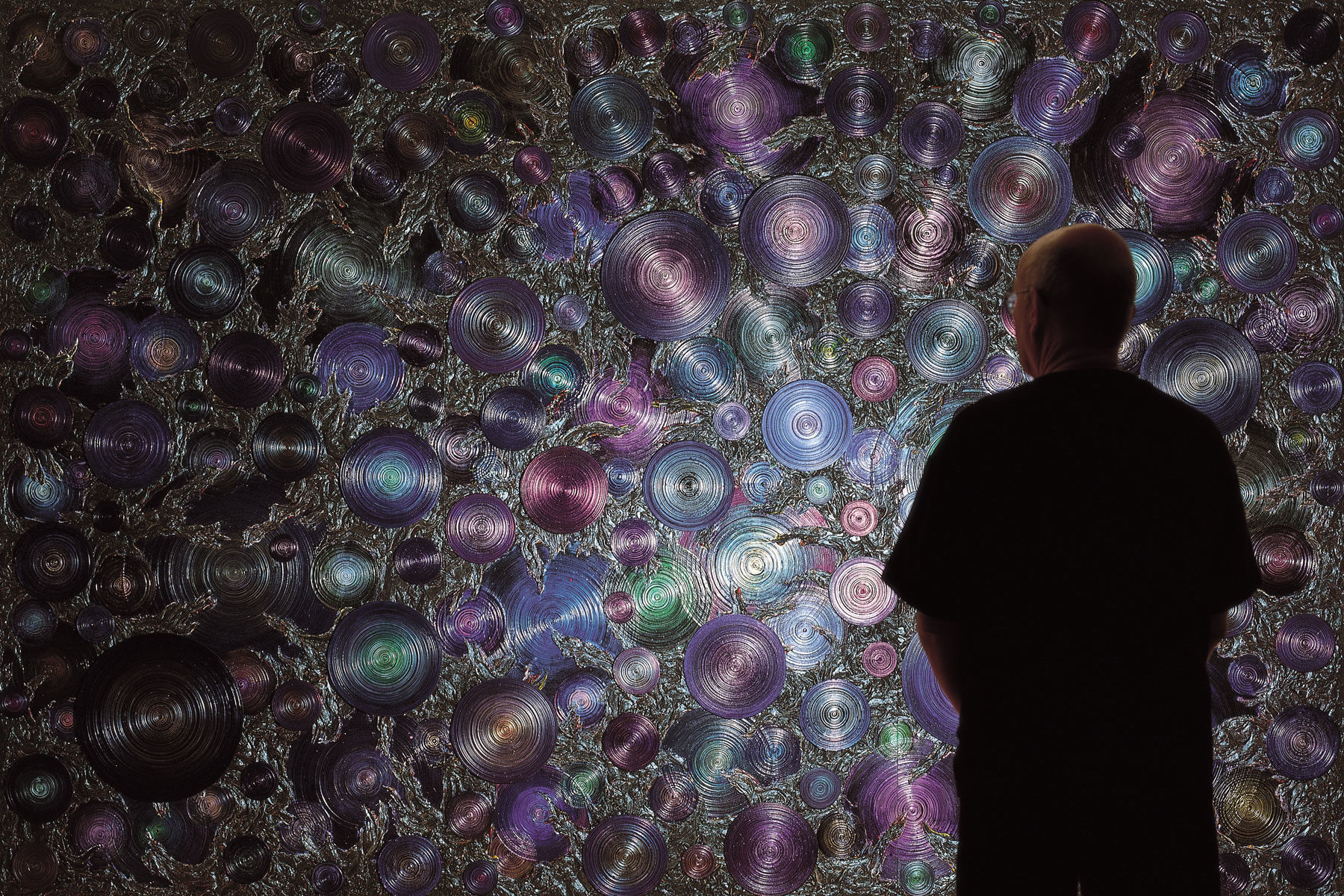

His technical approach to Hindustani music, more often than not, is born out of his experience of his painting, more than the other way around. Conversely, the musical take on emotional expression can be subtly discerned in his paintings. He has bent the musical idiom to his own creative vision and through this journey ‘[I have] … discovered my own medium’. The way that light embraces and charges the multitude of shapes and circles of Asher’s paintings does evoke the sensuousness of beautifully crafted notes continuously emerging from, and trailing off into, the ether. In doing so, the mind and thoughts are coloured with an emotional charge that captures us in its presence – and in the present.

‘If you listen to a piece of music there are not two people that are experiencing the same thing, I think it is the same with my work. It’s the wonder of it all that I’ve been taken by.’

Dr Adrian McNeil

Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies

Macquarie University.

References:

Asher’s work

Asher Bilu feature story from the ABC Sunday Arts show, broadcast on 1 April 2007 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3PJ-hnLdg_g

A feature on Asher Bilu, screened on the ABC Arts Show in September 2000 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h57hA85of5M

A shot clip of a concert by Ashok Roy (sarode) Gladwin Charles (tabla) in Asher’ s old studio http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g3bjD5Gc1iw&feature=related

Asher Bilu: Recent Paintings, The Art Gallery Pty Ltd, 1988

Space Place Space Time: Asher Bilu Paintings and Installations, New Street Publishing, 2010

Alap

A demonstration and explanation by Ustad Wasiffudin Dagar http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LxUD1LyAyp0

A recording of alap on sarode by Ustad Ali Akbar Khan http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S5q7ZLzfMac

McNeil, Adrian

Inventing the Sarod: A Cultural History Kolkata: Seagull Books, 2004

* All quotes of Asher Bilu, which appear in inverted commas, are taken from interviews with him on the ABC Arts shows in 2000 and 2007.