Asher Bilu

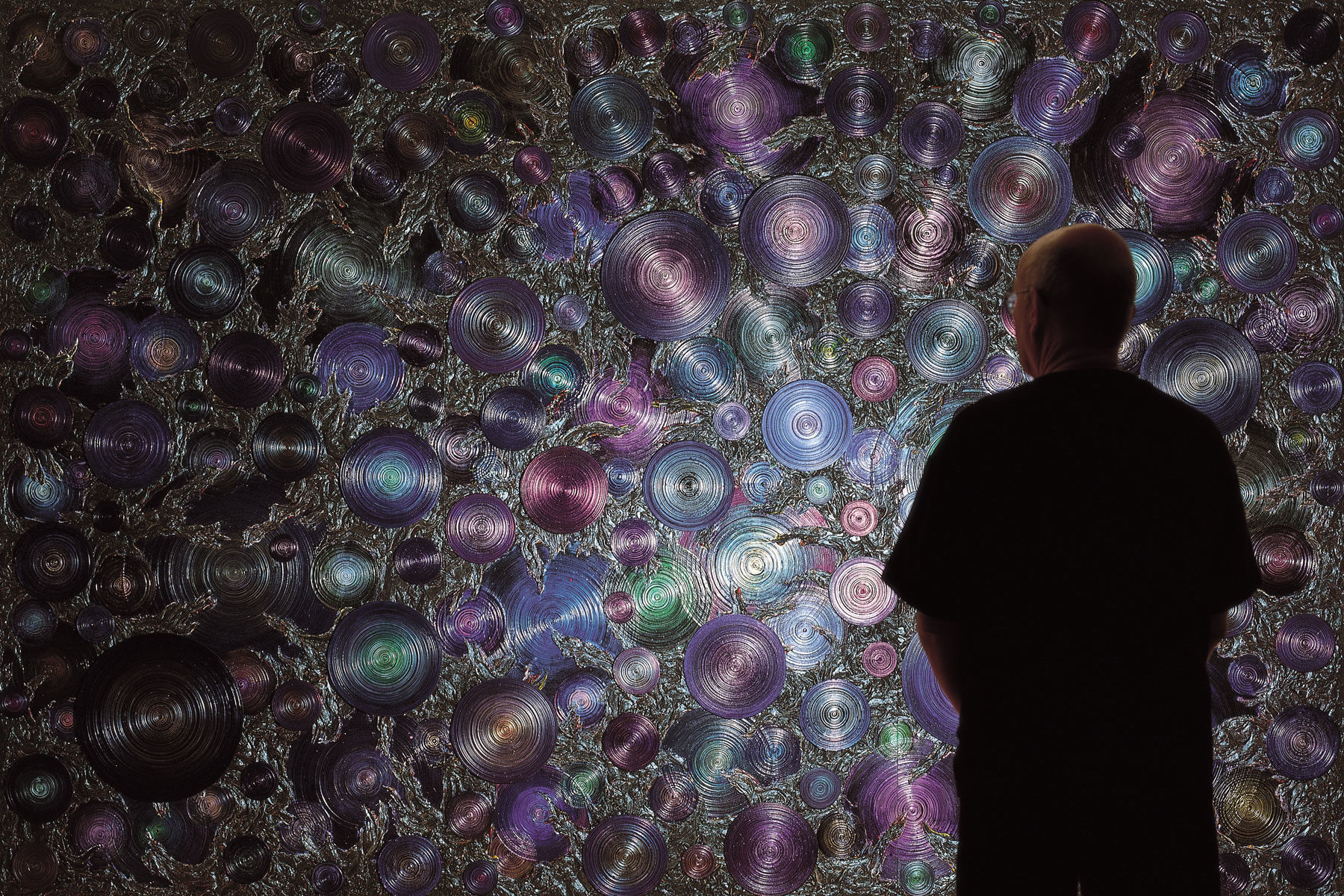

It is nigh on impossible to define Asher Bilu’s oeuvre. He uses drawings, paintings, sculpture, installation and, often, all of the above, in a single work. If he has a central rationale it would seem to be quite simply to capture the cosmos or, at the very least, to capture the wonder the universe can inspire. Bilu himself simply says, “Call it sculpture, or call it painting, my aim is to create visual ecstasies.”

Visiting Asher Bilu’s studio, home and garden is akin to walking into another dimensions – one delightfully cluttered with a morass of cultural bric a brac. His home, which he shares with his wife Luba, occasional grandchildren, visiting dogs and a semi-domesticated family of native birds, bursts at the seams with artworks. There are his own and those of their innumerable artists friends such as Ivan Durrant, Dale Hickey, Jon Cattapan, Gareth Sansom and Giuseppe Romeo. These are abetted with cultural detritus, items collected from around the world from India to Indonesia, Arnhem Land, New Guinea and Africa.

Their garden is a sculpture park, where Asher’s works complement those by other artists and sit amongst tree-ferns and towering trees. Sections of it remind visitors of the late Paul Cox’s acclaimed 1983 film Man of Flowers, which is apt – Asher Bilu worked closely as an art director many of Cox’s films and the Bilu home and garden acted as settings for that film.

Lunch had originally been scheduled for 12.30 until Luba Bilu realised she had made a terrible mistake – Robyn Williams’ Science Show was broadcasting on the ABC until 1.00pm. It seems that if there is one cardinal rule in the household it is that Asher gets to listen to the Science Show. Indeed, such zones as science, abstract mathematics, quantum mechanics and their ilk seem to sit alongside esoteric belief systems and art and music with equally passionate fascination for the artist.

Bilu was born in 1936 in Tel Aviv and, even after spending his entire adult life in Australia, still speaks with a strong hybrid accent impossible to categorise. Like most Israeli youth he spent a short stint in the defense forces and living on a communal kibbutz. He recalls as a toddler being allowed to play in the studio of the artist Batya Lishansky who lived in the same building “That was really my introduction to the world of art. There was a piano and paintings everywhere. I was playing in this world of visual ecstasies” By the age of eight the youthful prodigy was studying classical violin and becoming a master at chess. At 14, as a painfully shy youth he was sent to live at a kibbutz in the Jezreel Valley which demanded strict adherence to its socialist creed (“Great idea, wrong species,” he says of socialism.) The young Bilu could not conform and used his violin as a form of “weapon” to ensure people would leave him be. However he fondly recalls his art teacher, Rafael Lohat, helping him to recognise the “freedom of art.” “He would have us close our eyes and just draw, take the line for a walk,” he says, quoting Paul Klee.

In 1956, after finishing two and a half years in Israel’s mandatory army service, during which time Bilu’s parents had moved to Australia, the budding young artist decided to join them.

Bilu wasted little time in finding a studio in Melbourne’s St. Kilda Road and by 1959 held his first solo exhibition. Here he met Don Laycock, with whom he formed a life-long friendship, and renowned figures such as Georges Mora and John and Sunday Reed, which led to follow up exhibitions at the Reed’s Museum of Modern Art of Australia and Georges Mora’s Tolarno Galleries.

In the years following Bilu would win the cherished Blake Prize and join forces with his wife, Luba Bilu and artist Ivan Durrant to establish the independent artist-run gallery United Artists and work in intense collaboration with filmmaker Paul Cox (1940-2016).

Bilu recalls that when the director approached him to act as art director on Man of Flowers (1983) he accepted on the spot. “It was only after he left that I realised I didn’t have a bloody clue what an art director did!” he says with a wry, self-depreciating chuckle. Nonetheless the duo went on to collaborate on five further films: My First Wife (1984), Cactus (1986), Vincent (1987), Human Touch (2004) and Force of Destiny (2015).For Vincent Bilu painted 11 copies of Van Gogh paintings to be seen as originals in the film, pumping them out from a “nest” in his studio.

Working on films did not impede his other outpourings of painting, sculpture and installation, indeed art directing simply segued into what he describes as his overall raison d’être – that of “three-dimensional painting,” he says. “I want to use this language to express the beauty and the mysteries of our existence in an infinite universe.”

Indeed the words most often overheard when viewers visited such installations as the ghostly Heavens (2006) commissioned by the Jewish Museum of Australia, and touring to regional galleries in Victoria, the haunting Mysterium (2003) at McClelland Gallery, Langwarrin, Melbourne, Cosmotifs (2013) at Benalla Art Gallery or SpaceTime (2012) at Macquarie University Art Gallery in Sydney were along the lines of “awe-inspiring,” “wondrous,” “spooky” and “spiritual.”

At the time of writing, Bilu is frantically working on three major works for the impending BOAA (Biennale of Australian Art, to be held in the City of Ballarat, September 21 to November 6, 2018) where he has been granted three major rooms for installation.

There can be little doubt that these works are indeed imbued with a powerful element of the “spiritual,” but this coexists with an almost rabid fascination with the power of electronics and mechanics to articulate his adventure.

Indeed, this was succinctly captured by art critic Patrick McCaughey writing in The Age as long ago as 1967 on Bilu’s first Tolarno Galleries exhibition, describing his work, Sculptron 1 as “the first piece of electronic sculpture to be exhibited in Australia. Nothing in Australian sculpture could have prepared us for this remarkable and exciting event. It is a triumph for artist and technologist alike… It is indeed the total work of art.”

“It’s all an adventure,” Asher Bilu says as he feeds grapes to his native birds. “The wonders of the cosmos, the wonders of the world, all there for us to watch, the area of chaos theory, the Mandelbrot set, fractals, the sheer element of chance in nature, the mysteries in nature, the way one small thing happens here and has major ramifications over there – a world of visual ecstasies.”