A secular state and a national tendency to skepticism mean that the metaphysical impulse in Australian culture has historically been muffled, if not actually strangled. Where the cosmic turn is most consistently manifested is in visual art, especially in the work of abstract painters: in the dissolved and fragmented bodies of Ian Fairweather and Roger Kemp, in the gestural Zen calligraphies of Stanislas Rapotec and Peter Upward, in the crystalline lattices of Roy de Maistre and Godfrey Miller and the galaxies of Don Laycock and Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski, and latterly and spectacularly in the desert dreaming dots of contemporary Aboriginal painting.

One of the most consistent exponents of this ‘cosmic turn’ is Asher Bilu, who has pursued the numinous in works from his early, Blake Prize-winning painting I Form Light and Create Darkness (Isaiah 45:7) (1965, private collection) to his more recent, vast, mixed-media installations such as Sanctum (Luba Bilu Gallery, 1994) and Heavens (Jewish Museum of Australia and regional gallery tour, 2006-2007).

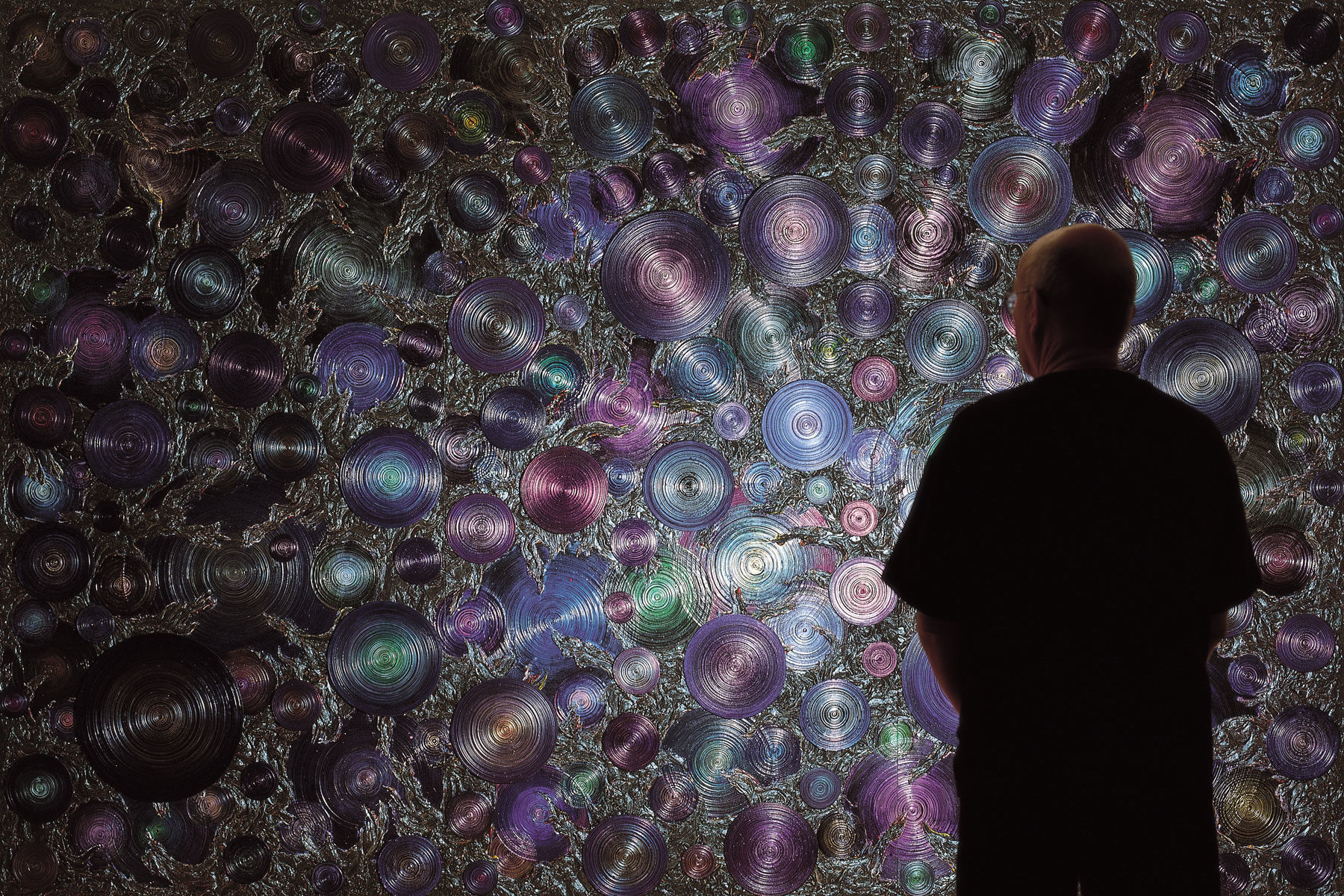

Since his earliest exhibitions in Australia in the 1950s, Bilu has worked in the aesthetic zone of Gödel, Escher and Bach, (1) that conceptual space where mathematics, art and music intersect, where repeated, inverted, complicated, fugal structures teeter on the edge of incoherence, while chaotic, non-linear dynamics produce orderly patterns, the elegant fractal geometry of the Mandelbrot set. Initially building his complex pictorial constructions from jigsaw-cut and painted layers of masonite and plywood, in the mid-1980s Bilu abandoned supports entirely when he began working with a new poly vinyl alcohol resin medium manufactured to his specifications. Beginning by laying down loopy and whorly and blobby fields of variously transparent and colorful paint, he then peels each dried skein of ‘eye candy’ off its temporary ground. In the large-scale installations, these cobweb-curtains of glister and colour are stretched and hung as walk-through architectures; in the domestic ‘paintings’ several layers are fitted one in front of the other within a multi-slotted wooden frame.

This produces the ‘astonishing effects’ memorably described by painter and critic Ronald Millar when the works were exhibited in 1985: ‘One … looks rather like a glass case packed with exotic tropical butterflies. Another … offers a family of pop-eyed surreal shapes that gaze at you from dark space, like odd creatures starring [sic] out from the night of the mind. Sometimes these mysterious … structures are studded with bright, staccato blobs, the colours fused together as if hoping to weld in place the uncontrollable threads of some mad electrical circuit. Others … are locked into a rich and delicate tracery very like a Mark Tobey painting. Bilu provides even more variety: some works seem to be created from re-cycled plastic toys; some resemble unplayable pinball machines; some are tightly stretched and looped and woven as if by mechanical spiders.’ (2)

All these resonances are to be found in the present work, and more: sweets (humbugs and lollipops), amoebae, Murano glass, the paintings of Joan Miró and Paul Klee, shooting targets, the ‘Magic Eye’ 3-D illusions so popular in the early 1990s. Above all, the work is a multi-layered dreamscape of eyeballs, with each colourful iris, each dilated central pupil staring out at the viewer. It has the look of an array of nazars, those popular Medierranean charms against the evil eye. In fact, as the artist himself implies in the title, The Eyes Have It is a meditation on vision through vision, a physical model of the paradox of spiritual revelation, where the seer and the thing seen become one.

Perhaps the last word should be left to Bilu’s friend Brett Whiteley, that connoisseur of altered states both mental and artistic, who described the work and its affect with some precision: ‘…The Eyes Have It … has an uncanny complexity to it, for it forces the eye to swim around certain vortexes of form – almost sucking you or pushing you before drowning, in the prickling surrealism that such forms instantly induce on the memory, so that one loses and regains the feeling of where the matter starts or finishes, like the transience of OP. It is a wonderful feeling looking at this (Boschian) Judgement Day, for only occasionally are you reminded of how far you have gone in from where you got lost, as it were …’ (3)

Dr David Hansen

Senior Researcher and Paintings Specialist, Sotheby’s Australia

November 2012

Article courtesy Sotheby’s Australia

(1) See Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Basic Books, New York, 1979

(2) Ronal Millar, ‘Paintings, only in the sense they are framed’, The Herald, Melbourne, 11 July 1985, p. 22

(3) Brett Whiteley, ‘Foreword’, Asher Bilu: Recent Paintings, The Art Gallery, Melbourne, 1988 (n.p.)