_______________________________

First exhibition: Dalgety Street Gallery, Melbourne 1960

Israeli painting much like ours

Alan McCulloch, The Herald – World of Art

In that it symbolises a new culture in a new place, Israeli painting has something in common with Australian painting.

But Israel is a country of ancient though nomadic traditions and its present population is descended from an ancient race.

Thus in Israeli art we expect to find a fusion of old and new, of East and West.

The paintings of Asher Bilu, a young Israeli painter, reveal many of these qualities.

They are on exhibition at 43 Dalgety-st, St Kilda.

The spirit here is Eastern as well as Western and contains the ancient flavour of the scriptures, but the manner of presentation has the freshness and excitement of today.

A lot of the emphasis is on textures. It is the textures for example which connect the paintings to their theme.

Plaster and paint, melted wax applied to metal, the raised surfaces of materials, the services of these and other devices have all been co-opted to the cause of expression.

The artist is playing a dangerous game; but just when all appears to be lost he comes to light with a piece of pure paining which carries him through.

“Celebration” (17) is a notably luminous work in which considerable mastery of structure and color is evident.

Equally noteworthy is the lost and found quality of “Conversation” (11) and the integration of form and color in “City” (10)

_______________________________

Bonython Galley Adelaide 1962

This medium is easy for Bilu

Geoffrey Dutton

The name of Asher Bilu is practically unknown in South Australia. He is not represented in the Tate Gallery exhibition of Australian Art, and yet he undoubtedly is one of the two or three best abstract painters in this country.

His show at Bonython Gallery is effortlessly accomplished.

He is at home with all the latest techniques, but through the gritty, or hessian surfaces flow warm and subtle colors that show him to have a sensitive imagination as well as a cool brain.

A young man born in Israel, he already has a name overseas. He is going to London later this year – fittingly enough for his work is completely in the international idiom, its sophistication at home anywhere.

With commendable honesty he gives no fancy names to his paintings, but simply calls each one “Painting”.

Thus, although one may see the constellations in one, a haloed figure in another, or a prehistoric bull in another, this is the viewer’s responsibility leaving Bilu to make his claims sheerly in terms of form and color.

Though he has a few dominant motifs, such as dark moons or intersecting parabolas, there is no handy key to his work. It should be looked at. It is very good, indeed.

Raised Rough Surfaces: Geoffrey Brown, RSASA Gallery; Asher Bilu, Bonython Gallery, Adelaide

Earle Hackett The Bulletin August 18 1962

Two young men who like to raise or roughen the surfaces on which they paint are showing their work in Adelaide. Geoffrey Brown is a local boy. Asher Bilu, born in Israel, has brought his pictures to us from Melbourne and so he bears an exotic ready-made aura which the local Mr Brown has not.

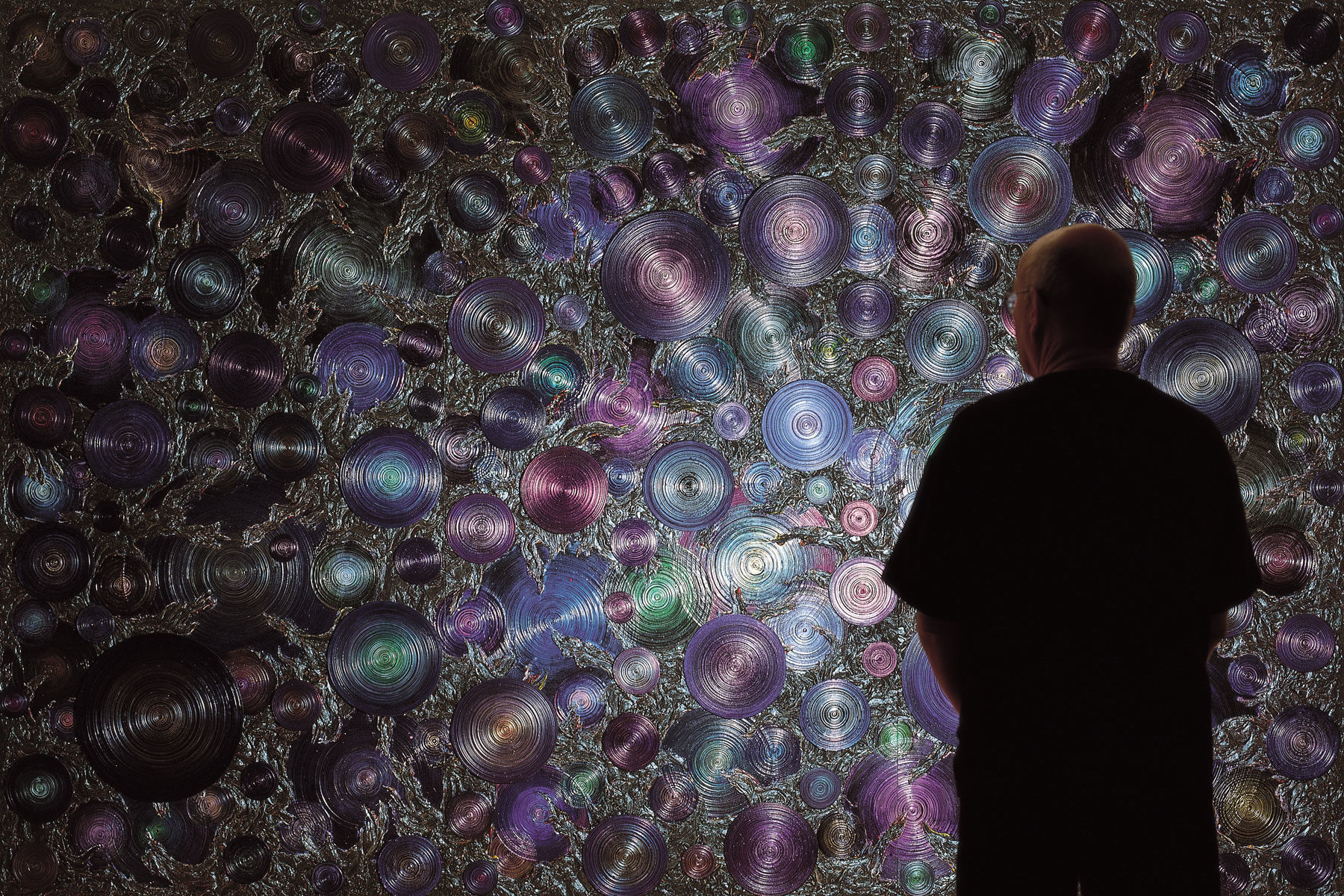

Mr Bilu’s paintings feature a central disc or focus around which there are mysterious swirlings of color, raised or burnt surfaces, and a few strewn threads. Some are on velvet. Another is on a scroll. There are only dates in the catalogue; no titles, no prices. One gets the impression that here is a young man innocently searching for new effects, and finally finding some which are beautiful, but that really there was more pleasure in creating these works than there is now in looking at them. In so far as they are “about” anything they are reminiscent of celestial objects and fiery galactic disturbances evolving out of chaos. The prices, on enquiry, turned out to be appropriately astronomical.

_______________________________

David Jones Gallery, Sydney 1962

Gyrating Worlds In Space

By Our Art Critic (sic) Around the Galleries – The Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday June 21, 1962

Accomplished and varied abstract paintings of a rather familiar “cosmic” nature by Asher Bilu are showing at David Jones’ Art Gallery.

The sun, moons and gyrating worlds in the vapours of outer space by this young Israeli artist are painted with a sure command of technique – a technique that involves disturbed textures of plastic-based paint. The colours and tones of the larger paintings are rather too close in value with a resulting weakness and lack of character from the diffusion that makes the forms appear to melt into one another.

The best of the larger works are Nos. 18 and 20, and of the smaller paintings, 5 and 11.

Fair and otherwise

Nation July 14, 1962 (P19) Art

To David Jones Gallery, Asher Bilu, a young painter from Melbourne, brought an exhibition (sic). At 25 he commands a formidable armoury of techniques; his hard pastes and iridescent glazes are burnt, slapped, coaxed and attacked until they resemble, not paint, but water-deposits on a stone or the patina of bronze. And yet, despite its bravura, this performance is self-effacing. It does not conflict with the overall “presence” of the painting. Thus Bilu’s surfaces are exotic, but not emptily spectacular. Often as thickly encrusted as Tucker’s or Lynn’s, their sliding, dreaming colours are atmospheric and do not induce a feeling of earthbound monumentality; nor can one associate with them the sense of physical tragedy one gets from a Tapies.

In the general context of non-figurative Australian painting, Bilu is unplaceable. He does not look at the landscape; he would rather contemplate the planets in their courses, or the configuration of a beetle’s wing. Meditation is the key word, and Bilu appears to have an affinity with Tobey and other metaphysical abstractionists of the West Coast, revealed not in his forms (which are quite unlike Tobey’s) but in the attitude to painting as an extension into the unknown, which lies behind them. Thus, he is generally at his best when he does not try to push a figurative image through the forms. His big suspended orbs, pulsating among veils of infinite light, become rather banal when you think of them as suns or moons. Though occasionally an area (or, less often, a whole painting) breaks down into inchoate, light-filled mist, Bilu has greatly advanced from the somewhat chichi ornamented circles he was painting on velvet in 1959 and 1960. Here is an undeniable talent, one of the few “new arrivals” in whom one can, I think, have full confidence.

_______________________________

South Yarra Gallery, Melbourne 1966

Daring painter draws on cosmic themes

Patrick McCaughey Art Notes The Age

Asher Bilu (South Yarra) is a daring and ambitious painter. Drawing his themes from the universe itself, he fashions cosmic images of the creation of matter.

The difficulty of painting such conceptions must be obvious. For in attempting these subjects, the artist must convince us of their reality. Only the most reactionary could fail to be moved by Bilu’s current exhibition. The luminosity of these paintings extends our imaginations and brings us to a new awareness of our total environment.

What convinces us most about these paintings are their tactile qualities. These fiery worlds have a graspable, physical presence on the surface of the work.

The cosmic drama of matter becoming a form provides the structure of Bilu’s artistic experience, for in the paintings the created form itself then becomes a textures weighty object.

These are not just fantasies of the heavens (a sort of super science fiction) but a total experience, communicated by rich painterly textures.

Bilu reinforces the reality of these scarred and pitted images through his dynamic conception of the cosmos. There is a continual sense of movement, formation and disintegration.

In Aion (1) the mass struggles to become a circle and there is a momentary allusion to a struggling figure. A gash of paint in Sublunary inaugurates a new series of forms.

This restless drama provides him with a theme of sufficient scope to match his sheer painterly qualities. He is important and not to be missed.

_______________________________

Tolarno Galleries Melbourne 1967

TWIN TRIUMPH Electronic sculpture comes to town

Sculptron 1 Patrick McCaughey

At Tolarno Galleries this week Asher Bilu and Tim Berriman are exhibiting their Sculptron 1, the first piece of electronic sculpture to be exhibited in Australia.

Nothing in Australian sculpture could have prepared us for this remarkable and exciting event. It is a triumph for artist and technologist alike.

To understand its full significance we must set it into a wider context of 20th-Century art. One measure of its significance is that we are compelled to set it into such a context. No local context would be adequate enough. It deserves no other assessment than as a contribution to one of the central developments of 20th-Century art: Kinetic art.

Over the past five years this art has assumed great importance on an international scale. It is not a school or movement in art as the cubists or surrealists were. It is rather a new type of art that is being developed.

Instead of seeing the work as a finite, static entity, the kinetic artist develops the new idea of the work of art as a continually changing and developing process.

Many kinetic artists do not depend on the resources of technology for the creation of their movement, for the real potentialities of the art lie in the promise of a creative relationship developing between artist and technologist.

Here we come to the significance of the Bilu-Berriman Sculptron.

Only electronics could have made this work possible. It depends entirely on technology for its effect and meaning. It is a shared and equal conception between artist (Bilu) and technologist (Berriman).

At first sight the work is remarkably simple. Seven radar cathodes, each looking like small, circular television screens, sprout like branches from a stainless-steel stem. On these seven screens abstract light images are in constant movement. One image resembles a star flickering and exploding. In another a circle slowly and spasmodically oscillates; in another a tangled skein of light endlessly weaves and criss-crosses over the screen.

The sounds in the environment of the sculpture create and control these images. The Sculptron responds to the most distant and the most immediate sounds. Cars passing outside, a door slamming or our conversation changes and regulates the images on the screens. At all points the Sculptron responds to its environment, changing as its environment changes.

As spectators we are engaged both imaginatively and physically. Our presence before the Sculptron changes its images and so on.

This is one of the central qualities of the work – that it involves the spectator in a more immediate and living way than static works of art. Hence the Sculptron is almost an apotheosis of 20th-Century art where the work becomes an event in which spectator and work are bound together.

Sculptron 1 challenges many of our pre-conceived notions about art. In one way it disintegrates from into movement – yet the movement itself assumes a pattern but never fixity. In another way it is an impersonal machine for making images – yet it is immensely responsive to its world. it dwarfs the spectator but does not menace him.

It is indeed the total work of art.

_______________________________

Clune Galleries, Sydney 1969

Impact in Cosmic Visions

James Gleeson The Sun 12.3.1969

One of the highlights of last year was the appearance of Asher Bilu’s mystical “Maha Yoga” and his one-man show at Melbourne’s South Yarra Cellars (sic).

It was shown in Sydney at the Transfield Prize Exhibition at the Bonython Gallery, last November, and now, supported by nine other major works, it is one of the highlights of his one-man show at Clune Galleries.

In Melbourne, it dominated his exhibition; here it is only one of several paintings of equal or greater excellence.

For many, a picture justifies itself if the interplay of colour and form evokes a pleasurable sensation, and it is possible to view these paintings and enjoy them as no more than exceptionally fine exercises in decoration.

However, there is much more to Bilu’s paintings than their power to enchant the eye.

It helps to understand his art if we think of it as the sort of thing William Blake might have done had he lived today and accepted the conventions of abstract art.

For Bilu’s paintings are visions of cosmic forces expressed in a non-figurative pictorial language – perhaps the only language really capable of communicating a notion of the powers and energies which shape the universe and which animate the spirit.

In his revolt against the limitations of reason and logic, Blake was obliged to express his intuitions and personifications in a complex mythology of his own devising.

The solution was basically a literary one. The full significance of his paintings only became clear if we were able to interpret his symbols correctly – and this often required a detailed knowledge of his private mythology.

Bilu avoids these limitations by speaking in the more open language of abstract forms.

He does not ask us first to identify the forms, and then to interpret them; he simply asks us to stand in front of his paintings and experience them as a visual-emotional sensation, in the belief that the mystical element in the work will be communicated through this direct contact.

After having had the experience we can begin to analyse its nature, but we do not arrive at the experience by a process of analysis.

Three of the most impressive paintings are black and white developments of the Maha Yuga theme called “Yuga 1, 11 and 111”.

Large, bold, nearly symmetrical and heavily-textured shapes are developed with a labyrinth of fine lines to suggest organisms of infinite complexity, but the work which really stands on a higher level of creative expressiveness is the fascinating “Purusha”.

It is hard to pinpoint the precise reason why it should make such an impact. Perhaps it is because the arrangement of forms conveys a sense of invitation.

There is a suggestion of a portal forming in the clouds, and beyond that, an intimation of something shadowy and enigmatic floating in a grey universe. A theme of peace and impending revelation ti conveyed.

The brilliance any mysticism of this exhibition makes it a very rare event in Australian painting.

Art & connoisseurship

Donald Brook Sydney Morning Herald 13/3/1969 Art Review

At CLUNE’S Gallery, Asher Bilu is showing a group of 10 paintings that roughly divide into two groups.

One set exploits the natural, if ambiguous symbolism of huge matt, sullen cavities into which – or from which – dismayingly abundant cataracts of material flow.

Sometimes it is a skein of stranded fibrous matter liked veined ectoplasm, and sometimes it is a congregation of jolly jelly-bean enamelled outsize sperms.

And the other sort of picture, sour as pitch and lime, employs the more arbitrary symbolism of a mandala-cross, the proper reading of which will perhaps – and perhaps not – be evident to Sanskrit scholars, from the titles.

The physical surfaces are fascinating: there is no question that Bilu’s way with textures, in the whole range from parched black pumice to slime, is resourceful and ingenious. What disappoints one about the pictures is their spurious air of being pregnant with significance – a significance that trades always on remaining somewhere just outside one’s grasp.

Leonard French is a painter who often produces a similar effect, although on a sweeter basis of colour and a less dramatic range of texture. He too will sometimes bolster a banal pictorial idea with a symbol or a hint of Sanskrit, so that one has the outsider’s feeling in relation to freemasonry or theosophy or hippiedom: that if one joined one would surely understand. But join what?

The irritating trick is to present paintings as if they were quasi-linguistic communications: and to rely on the natural modesty of an audience for the judgement that the content must be unfathomably deep.

Art of rare mystic quality

James Gleeson The Sun-Herald Sun 16 March 1969 World of Art

It is possible to visit the Clune Gallery, look at Asher Bilu’s 10 abstracts and leave the gallery having had a completely satisfying aesthetic experience without once wondering if they meant anything.

Generations of abstract painters have conditioned us to look at their works without question marks.

We look, and if the interplay of colour and form succeeds in creating a pleasurable sensation we assume the aesthetic transaction to be complete.

To ask an abstract for its meaning has become a token of philistinism.

However, Bilu is an abstract painter with a difference and if we fail t search his paintings for their meaning we will have missed the quality that makes him one of the rarest of Australian painters.

Behind each visual delight there is a meaning waiting to be discerned.

We may not always understand its implications, for Bilu is a visionary and a mystic, but if we stop short at the point of visual ratification then we have missed the most essential point of Bilu’s art.

This does not mean that there is anything remotely “literary” in these paintings. They are not pictorial translations of notions which pre-existed as a form of words.

It would be impossible to reproduce the exact significance of his paintings in any other medium simply because each painting is a raid upon the ineffable.

Each painting is an attempt to explore those realms of the spirit which must defy the easy access of words.

One can, of course, describe the overt presence of a painting like “Purusha”.

Imagine paint which conjures up a feeling of cloudy space, dark below, light above.

Imagine a series of horizontal and vertical bands forming in the lighter zone in such a relationship with one another that they suggest the mouldings which might frame a doorway, mouldings which are made of clouds or open sky or inexplicable shadows.

In the centre of this portal there is a sphere p dark above, light below – sometimes suggesting convexity, sometimes concavity, but holding within it a suggestion of mysterious movement.

It is easy to think of it as an egg in which life has just begun the process of forming itself.

It is equally easy to interpret it as the void made fertile by the galaxies.

The more we look at it the more apparent it becomes that the forms and colours are a vessel brimmed with meaning, but the meaning is like quicksilver which defies the purposeful grasp of reason.

If you reach for it in an action under the direct command of consciousness it will slip through your fingers.

If, however, you can empty your mind before it, it may so work upon your intuitions as to produce a sensation of revelation, even when it is impossible to say afterwards what it is that has been revealed.

Perhaps we can only describe the sensation as an intimation of something that lies so far outside the experiences of every-day life as to be incommunicable except in the terms devised by the artist.

One thing is certain – Bilu is no ordinary abstractionist.

He is a mystic and his art will always be incomprehensible to those who reject the possibility of a mystical experience.

Bilu paints soul, eternity

George Berger Sydney Jewish News 21/3/1969

Face to face with 10 paintings by Asher Bilu, one can more appreciate the reasoning behind Gleeson’s contention that Bilu’s Maha Yuga would have been a better choice for the 1968 Transfield Prize than Peart’s Bivouac.

Bilu, well known in our community as the first Jewish painter to win the Blake Prize, is currently holding his first one-man show in Sydney, at Clune’s.

Born December 1936, in Israel, he settled in Melbourne in 1957 (sic), and began painting full time.

Since 1960 he has held 11 one-man shows in Melbourne, Adelaide, Amsterdam and London; the British Contemporary Art Society bought one of his works for its collection.

It is difficult to classify Bilu’s work. It has an affinity with that of Tapies and the Spanish wall school, but in Parusha this has been subordinated to the illusory three-dimensionality pioneered by Ron Davis – it is a work of today.

However, Bilu’s technical brilliance, his penchant for la belle matiere, and even the stylistic developments, recede into the background and lose their immediate reality when one is confronted by the work itself, so strong is its spiritual impact, its magic magnetism.

Bilu borrows the terminology of Hinduist (sic) mythology for the titles of his paintings, and they fit well the intricate Oriental splendour of his concepts.

It is even formally possible to see an open lotus-flower in the series of five paintings facing the viewer on entering the gallery.

In Satoru, its four petals are richly coloured like an Indian sunset against the background of a slate-blue nocturnal sky.

However in Yuga 1 and 11 the sediment-textured chalk-whiteness of the lotus centre spreads outwards and threatens to engulf the petals , now coloured in a dry, matt black, whilst in Yuga 111 a black shade progresses from left to right as if intent to swallow up the whole of creation.

The texture – most likely the plaster-bed of gouged-out pebbles, crushed stone and sand – is so cleverly devised that it shimmers like beaten silver.

Maha Yuga, earlier seen in the Transfield selection at Bonython’s, represents the fourth stage of creation.

Here the lotus-centre flows down, and one can see it as the furry front of a hairy beast, perhaps the Abominable Snowman, while the creamish curled-up top-petal may form into the beast;s head.

Maha Yuga and Om are both the most painterly and most surrealist works on show.

One reminds of a brittle, disintegrating bone, floating in the evening sky.

The hard outline of the bone is eaten-up by the fiords and the soft texture of the sky shows relief droplets of paint like the hairy beast’s front.

They are not the uninhibited, impetuous splash marks of the expressionist, but highly selective, carefully planned and executed encrustations, like jewelled insets.

They remind in this of Roy Lichtenstein’s elaborate White Brush Stroke 11 in Two Decades of American Painting seen in Sydney. They decidedly are Post-Expressionist manifestations.

Asher Bilu is a naturalised Australian and a young artist of international importance.

Should his work not also be amongst the select few when the Contemporary Art Society sends work abroad? On the showing of the current one-man show, one would think so.

Discovering masterpieces in the lightweight arts

Elwyn Lynn The Bulletin March 22 1969

There is plenty of textural and linear decoration in Melburnian Asher Bilu’s work, but it is there as no mere additive: great canvas-engulfing forms, half coral, half breathing marine creatures, sprawl symmetrically in the middle of the canvas, those in the Yuga series growing a webbed claw at each of the four corners. The lines are thin, trace in white, and resemble primitive rock and bark drawings, but testify to the presence of something alive, at times supporting tentacles and at others the spirals and radiating ridges of shells. Cit ($1200), a pale, rather amorphous work, with a square in the centre, is rather like a geometrical Turner. The central mass gives birth to shell, without Venus, and the delicate ridges in the outer area give us a view from within the shell.

If it is the essence of fragile structure, the three Yuga works squat like fossilised amoebas; they sprawl, but the white markings in Yuga 1 and 11 (each 72in x 72in and $3000), moving in complex spirals and meanders, give the life, those at the edge of Yuga 11 becoming almost skittish.

Bilu has always been a symbolic texture painter: he is not concerned with texture as a matter of depth and surface; he does not look upon texture as the primordial substance , as does Tapies; he is a symbolist, regenerated, from the end of the last century. Porous areas of lava are filed back, pale surfaces washed with pale color, tear-like nodules trail gossamer threads, and sprawling bodies bear delicate and intricate designs for a purpose. In Devaloko ($750) an oval, crushed, pitted, and shorn flat, sinks into a grey crust. It ought to look like the dark side of the moon,, but the holes and lacerations are so placed that they take on a slow, almost indiscernible movement. He makes symbolic images rather than conventional icons, as do a lot of artists outside this thoroughly conformist country (art-wise, people who venerated hard-edge abstraction a year ago are almost to the ground with boredom). Bilu is after theme, content, message, or what you will. Sometime the apparatus creaks a little under the pressure, as in Parushu (72in x 72 in $1000) with its grey, ashen globe enclosed in squares and floating over an eroded, porous terrain, most impressively rendered.

We know all the accusations: literary, over-theatrical, irrelevant to the mainstream, and so on, but he survives these structures and certainly does not aspire to fine or decorative arts.

_______________________________

Holdsworth 1970

A sense of elegance

James Gleeson The Sun-Herald World of Art 10/5/70

Asked to name the most elegant and sophisticated of all our completely non-figurative artists, my choice would be Asher Bilu.

Asked to pick the most serious and profound artist from the same category, my choice would still be Asher Bilu.

Normally, when one mentions elegance in art, the concept becomes tangled up with notions of smartness and fashion – but this is not the way in which Bilu’s paintings are elegant. It is, I fact, quite hard to say why they do give one a sense of elegance – except that they have the qualities of order, neatness and inevitability that we encounter in mathematical equations – qualities which cause a sort of mental satisfaction because they are symbols of our belief or at least our hope, that everything is ultimately based on law.

Bilu, in his current exhibition at the Holdsworth Gallery, has increasingly restricted himself.

Colours are usually monochromatic, or at most a duet worked out in the closest of harmonies; shapes tend more and more to the absolute perfections of the circle and the square, while the designs rest upon the restfulness that comes from symmetry, ordered repetition and the fulfilment of expectations.

Of course we can accept these paintings as abstracts made that way because abstraction is an accepted convention in the art of our time.

Hundreds of contemporary artists do paint abstract paintings without considering it necessary to arrive at their forms or shapes through a process of abstraction from specific experiences of reality.

However, there is something in Bilu’s paintings, an intensity, a high seriousness and a concentration which causes the viewer to think beyond the immediate visual experience and to analyse his sensations more closely than usual.

For one thing, the order in the majority of Bilu’s recent paintings is a kind of absolute order. It isn’t a delicate balance quivering finely in a knife edge. His organisations never suggest the astonishing skill of a juggler who must exercise all his control in order to maintain the precious but precarious harmony – his order is of the kind that carries no suggestion of a disrumption (sic) or of an alternative.

We come to think of them as abstractions – not just as abstract paintings. But abstractions from what? From what are they derived? What are they saying?

Surely they represent an awareness, an overwhelming awareness of the existence of order. They celebrate he fact that the Universe can be understood as design and not as a vast accident.

Behind everything there is the wonderful implication of law. And Bilu has had to use a pictorial language derived more from mathematics than from visual experience in order to express this awareness. He has had to express himself in a pictorial equivalent for a mathematical equation.

He is an intense and serious artist, and yet his paintings are not cold or remote.

Few artists can match his sensuous delight in the material properties of their medium and in the ability to make a still surface seem to move, and although he often chooses to restrict his colour most severely, he invariably uses it with the utmost subtlety and sensitivity.

Here, in Asher Bilu, we have an abstractionist for all seasons.

Holdsworth Gallery Sydney

The Bulletin Vol 92 No 4704 16 May 1970

ART/Elwyn LYNN

Dignified Death IN TWENTY-FOUR arresting works, all black and white and grey, except for some mysteriously veiled colour and two in blazing red and yellow, Asher Bilu, who has long been devoted to evocations from the time-pitted rock and scorched lava beds, transforms the Holdsworth Gallery into a museum for memento mori. It is not the white, fossilised remains with their masses of infinite white lines in Yuga (72in x 72in, $3000), the funereal graphite discs in Graphite 4 (72in x 72in, $2000) or the eroded moons, as still as any stone , in Graphite 6 (54in x 54in, $2000), that induce the sense of awesome, majestic and dignified death; it is the absolute emphasis on self-containment, of imprisoning the forms and, paradoxically, suggesting that there is no life outside these dark and beautiful icons, for, like great tomb sculpture, they breathe with the life of those commemorated. The ambivalence of his symbolism is on every hand. Take, for example, the graphite disc, ringed with rough battlements, owned by the Melbourne dealer Joseph Brown: the centre could be taken with its tiny ridges to be a long-playing record of gloomy metaphysical poetry or a turret partly protected by earthworks and about to face whatever comes across the black terrain that is essential to Bilu’s imagery. Or take his astonishingly beautiful and haunting Circle 2, which looks like a moon made of ground coral, half of it whitish, as though raked by pale light, and the other half, after enthrallingly subtle gradations, becoming the dark side of the moon. Life’s circle, as it were, is fragile, full of holy light as well burnt-out ashes of despair. It’s a notion continued in such works as Graphite 6, where two curdled moons are reflected below in the shape of two glinting discs; the nine discs in Graphite 4 so transfix one with their mesmeric insistence that one does seek relief in a square with a raised circle that looks like a shield, its grey surface-traced, as it were, by the activities of marina creatures, and dredged from the sea. It is an exhibition of most haunting, memorable and mysterious images, even if Asher Bilu’s desire to bring all to a grim finality seems obsessive.

_______________________________

Bonython Gallery, Adelaide 1971

Bottleneck openings

Ivor Francis The Sunday Mail

Distinguished Israel- born artist Asher Bilu at the Bonython.

First off the mark in this weeks exhibition stakes was Asher Bilu, now settled in Melbourne. He has been attracting considerable attention since winning the Blake Prize and then the $9,000 First Leasing prize, which was shown in Adelaide last year.

His latest paintings are remarkable for their illusionist effects of flooding light and stereoscopic shadow on burnt synthetic resin and pigment-powdered surfaces, which resemble pottery rather than paintings.

“Permeation of Permutations” and the sun-warmed golden “Patterns and Simplicity” are fine examples.

Light shines down from an overhead battery of gallery lighting, but it also shines up with equal intensity, although there are no floodlamps below. The glowing colors are not fluorescent or otherwise luminous, which would explain the mystery; it is their purity and the artist’s skill in handling them that does the trick.

Think of yourself on a lifeless moon which millenniums ago was inhabited by a master race descended from the sun. The sun-gods have long gone with the air that is no more, but their marks remain indelibly fused into the dry, pitted primordial rocks. Does Bilu reflect his own ancient racial lineage?

This is how you feel about his work at the Bonython; it is what you get out of “That Which Is.”

You can even observe the shape of the sun-god’s artefacts – the design of a dome, for example, burnt into the heart of time, like “Formation of the Noonsphere”.

Bilu proves that an artist’s sheer inspired delight in making materials work for him in the process of turning them into something beautiful to see and feel is a valid expression of experience.

Timeless mystique

Elizabeth Young The Advertiser

It is almost 10 years since an exhibition of the work of the young Israeli-born artist, Asher Bilu was shown in Adelaide.

In his new show now at the Bonython Gallery, North Adelaide, we see the intervening years have brought a consistent development, a refinement of the elements then apparent.

An interest in texture, in new techniques, in abstract shapes and shy color has become an assured and personal control of media and an authoritative statement through symbols.

These works can scarcely be described as paintings, though framed and hanging: in their emphasis on tactile quality they approach more sculptural relief.

They are textured as if by time, like an old stone wall or pitted volcanic rock, and the organisation of the engraved symbols, combined with a restrained sensitively controlled spraying of color creates in each a timeless mystique.

As one moves, so the picture changes; edges sharpen or recede, color glows, becomes iridescent, darkens, but idea is always dominant.