_______________________________

Realities 1979

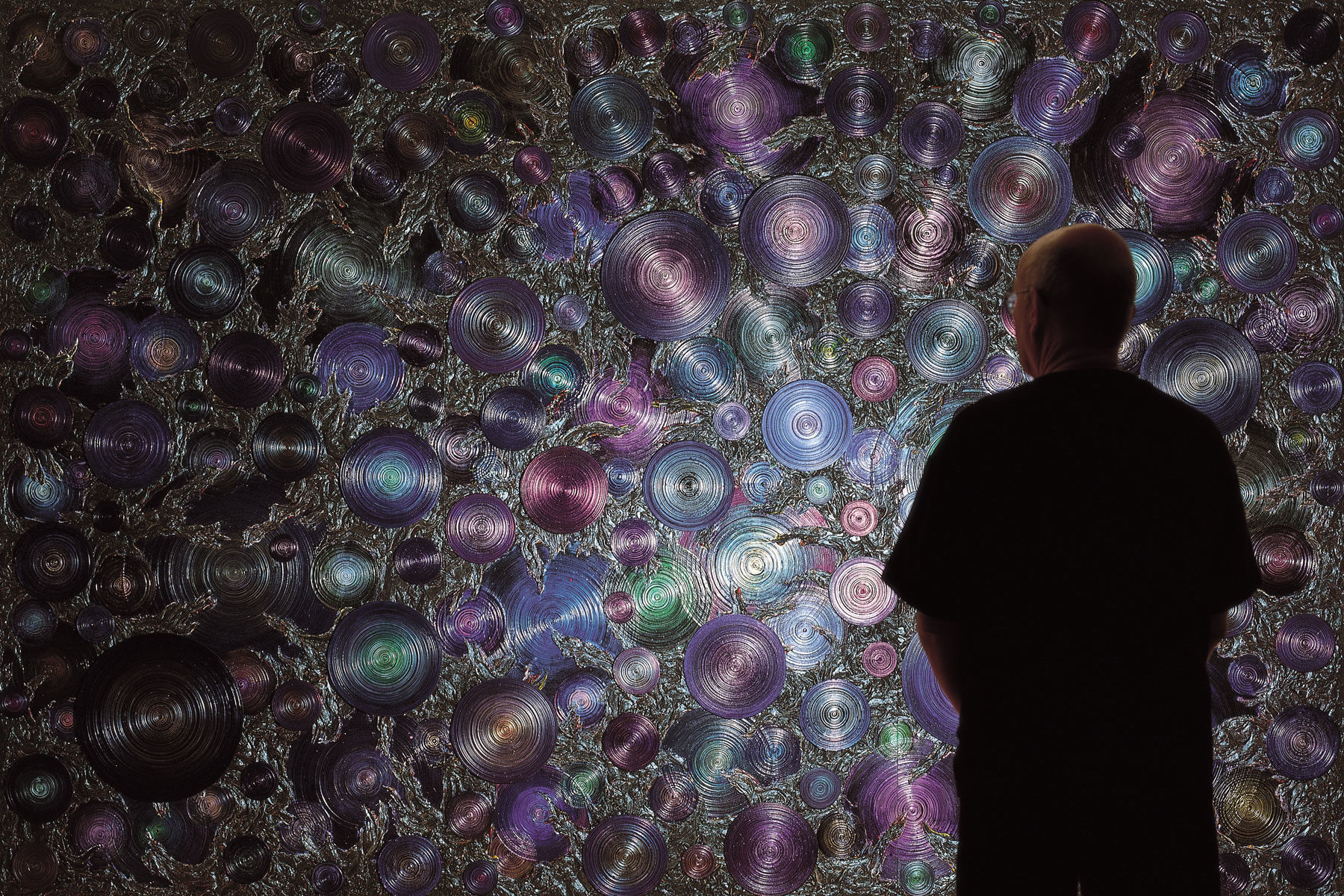

INFINITIES

Beautiful … on the high notes

Jeffrey Makin The Sun Wednesday Nov 7 1979

It is just possible that Asher Bilu, who opens today at realities, Toorak, is one of the few truly original artists now working in Australia.

The jigsawed intricacy and complexity of his constructions is staggering. Each piece is flatly shaped out of plywood, painted, then like a piece of jigsaw, is fitted or juxtaposed with hundreds of other fragments.

Bilu’s end result is a rich, multi-faceted three-dimensional texture that has no compositional hierarchy or emphasis.

In close the effect is chaotic. Confused. But read at a distance Bilu’s eccentric carpentry unifies into an almost Zen Buddhist contemplative calm.

The music (which Bilu also composed) that accompanies the exhibition is also lacking in emphasis. It has an Eastern monotonal chant quality to it.

Like Bilu’s paintings there’s no real beginning or end, just a droning abstract improvisation.

“The Dream” is the most successful piece, although I’m sure Bilu doesn’t see it that way, but simply as part of a continuing thematic experience.

Yet in spite of the artist’s intention, there is good and bad art, as there are good and bad experiences.

Like his life, Bilu’s art consists of extraordinary highs, and extraordinary lows. The Dream” is one of his highs, while “White for Brett” is struggling to get itself above the level of frustrated fretwork.

It’s this inconsistency that suggests that Bilu’s art is out of his control. It’s obsessed, intuitive. And so immersed in itself that it’s unable to be self-critical in a formal detached sense.

Nevertheless when Bilu hits a high note he delivers it beautifully, and within the context of Australian painting he comes across, like Ken Whisson, as a rather eccentric, inconsistent original.

Bilu shines in the dark

Graeme Sturgeon

Melbourne (sic) Asher Bilu is one of those artists who pursue their own course uninfluenced by the vagaries of contemporary fashion.

His exhibition at Realities Gallery, his first for seven yeas, shows the degree to which he has already moved away from straight easel painting and suggests that he is attempting to create an emotional experience as much as an aesthetic one.

In contrast to the usual practice if ranging paintings in a regular line against the immaculate white of the gallery walls, Bilu has turned the gallery into a darkened shrine. The works, as often as not, stand on the floor, but because of the way they are constructed, appear to flow out from the wall into the spectators’ space. Each is lit independently by powerful spotlights which force up the strong shadow patterns cast by the layers of fretted hardboard from which each work is made. The technique is incredibly elaborate and painstaking.

The entire surface of each work is uniformly fragmented, that is sawn into a thousand irregular shaped pieces, painted and reassembled to produce a whirling labyrinthine jigsaw puzzle. The finished works belong neither to painting nor sculpture and, given the theatricality of the presentation and the accompanying electronic music, composed and performed by Bilu, it is reasonable to assume that his intention was a total, enveloping experience rather than the contemplation of a single work.

To do this is still possible of course and works such as White for Brett and The Journey would probably be better served by being seen apart from the rest of the show. To step into the darkened gallery and be surrounded by these vast objects, glowing and pulsing in the gloom is a enticing experience but the strong impact of the show might well be because of the extravagant complexity of the technique coupled with the mysterious presentation of the works, not because of their intrinsic quality.

For all that, it is an impressive exhibition. Certainly it represents a new direction for Bilu and one which needs some appropriate occasion or location to allow him to develop the complexities of his concept to its fullest extent.

Mary Eagle The Age Wednesday November 14 1979

Either you do or don’t accept that the taped music (by the artist), darkened gallery, spotlights, and meditation couch, are relevant in considering Asher Bilu’s eight ponderous paintings at Realities Toorak ($6000 – $20,000).

The gallery looks like a scene for a séance or a temple of the occult.

Bilu does not appear on the scene, but the marriage of his own music to his own paintings does put him on the fringes of performance art.

I think of Bilu as belonging with the masculine cosmics of the 1960s – Lawrence Daws and Donald Laycock. The spaghetti squiggles and cosmic swirls of this exhibition maintain the tradition.

In the three-dimensional works, curve, cut-out and painted sections of plywood are all over the place, propped out on wooden plugs criss-crossing each other, totally obliterating any idea of central image.

They are dizzily alive in real space, painted in bewildering metallic colors and sparkling with silverfrost.

This show – six years in the making – forces one to respect its integrity, but I cannot like the works, except for the comparatively Spartan “White for Brett”.

STUNNERS! Bilu’s art for a temple

Alan McCulloch The Herald

At realities are eight huge works by Asher Bilu, done in enamels, casein and resin on plywood, some constructed from hundreds of related pieces cut from the wood with a fret saw.

They are as overwhelming in their visual impact as a first glimpse of the cupola of the Huida Gate, Jerusalem.

While at first they may seem to equate with science, modern technology, international abstraction, contemporary Spanish texture painting and so on, these are not the zones to which spiritually they belong.

Their spirit is entirely Jewish, as steeped in stylised ritual as the title page from baya’s 15th century Commentary on the Jewish Bible.

The paradox in this show is that tumult and serenity appear to have been united to form a harmony.

This in the large Spill Out (2), the action of the torrential cascade of silvery cut-outs is halted somehow within the curve of the façade to produce in the end an impression of stillness.

Nor is this stillness disturbed by the scintillating play of light as it penetrates the profuse branches of small caves and hollows.

Largely because of the sculpted surface and its lighting, White for Brett (3) challenges Malevich’s famous White on White with more success than usually attends this gamble.

Colors become richer and more varied in Nothing is Lost (7) and The Column (8) might have been inspired by the vertical forms and soft-edged colors of a Rothko.

The background music and special lighting affirm the mood of the exhibition and emphasise further that this is an art for a synagogue or temple.

_______________________________

Tolarno Galleries 1981

Robert Rooney The Age 25.3.1981

Asher Bilu’s high-kitsch abstract constructions at Tolarno Galleries, South Yarra, are complex Pollocky pop-ups, made from jug-saw off-cuts dripping with the nastiest bubbly resin imaginable.

In the smaller constructions, his swirling clef-like shapes, French curves and “white writing” are kept under control. They are to my eye the least offensive.

A large blue forest of waxy stalactites has a surface like tinted Santa Snow. Another work consists of fancy hot pokers covered with luminous orange that glows like an artificial fire, Ugh!

_______________________________

United Artists Gallery, Melbourne 1982

AMAZE

Application and Colour

Ken Bandman The Australian Jewish News Art-Wise 12 November 1982

The dictionary defines the verb “to amaze” as “to overwhelm, to surprise, to astonish”.

The same book explains the noun “maze” as “a labyrinth” or “a winding movement as in dancing”.

Master artist, Asher Bilu, always experimenting, forever pondering and meditating about exciting new and different ways to experiment with paint, has now come up with a creation called A-M-A-Z-E.

It is, in fact, an overwhelming, a surprising labyrinth made from paint that astonished viewers as they wind their way through this fabulous fairy-tale of fantasy.

Two large curtains of paint – not painted curtains – curtains made of paint, each some 40ft long and about 10ft high, hang from the ceiling in curvaceous glory, glamorously glittering in a glistening grace of colours.

The lighting of the whole affair is ingenious and the total effect is nothing short of entering Aladdin’s wonderful cave.

It is a cave of moods: Some parts hang there as jewel-like promises, while others wear a slightly sinister air – imagine stained glass windows transplanted into a subterranean cave.

How was all this achieved?

“Plastol” is a water-based enamel paint, the invention of Mr Ed Marcus. The paint hangs together, is quite transparent and can be pulled off the base on which it is painted in practically one piece.

Asher Bilu has an inventive mind, as seen again and again in recent exhibitions. So, he hired a vacant factory and covered then floor in plastic sheeting.

Here, with superb ingenuity and artistic mastery he painted colours, splashing and throwing, crossing and recrossing, circling and swerving; always knowing – or, rather – hoping and anticipating, the desired effects.

When the whole thing eventually dried and was pulled off the plastic sheeting on the floor, it was rolled together and transported to the exhibition … and hung from the rafters … and that is how we arrive at this amazing maze.

The whole effect is stunning and brilliant.

But there are also some slight, but obvious flaws in its presentation. The whole curtain hangs on hooks from the ceiling. These should have been painted black to give the curtains a “floating” illusion.

Some additional pencil lights could have been used with even more theatrical effect and the beginning and end of the labyrinth should have been curtained off in black to highlight the effectiveness of the stunning A-M-A-Z-E curtain.

Asher Bilu whose work, both recent and present, cries out to be used effectively in theatre or film production, is without doubt one of our outstanding artists.

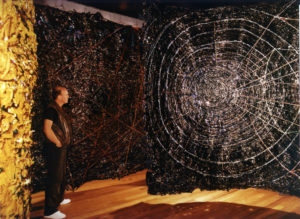

Memory Holloway The Age Wednesday 17 November 1982

Asher Bilu may be the archetypal image of the artist who creates for the sheer enjoyment of it all.

His current walk-through production which he calls “Amaze” is accompanied by loud droning computer created music, and theatrical lighting which shines through the back of a massive 35-metre long painting.

It is sheer Disneyland. The only thing missing is an air hose on the floor guaranteed to make your clothes fly in the air.

The artist says it took him more than 11 weeks to layer the tonne of paint which has dried into coagulated pools of drips. As he talks he thumps the painting which hangs by wires from the ceiling, as a salesman might kick the tyres of a car as though to prove its resilience and serviceability.

In a few seconds you wind your way back into the central coil, the labyrinth which was laid out by Bilu with a long bit of string (just like the story of Theseus and Ariadne). The spider webs and sunrays which punctuate the length of the painting wink away under the hot light and a fan circulates the air for anyone about to faint.

“If he’d had more space, he’d have made it even bigger,” his wife said on the way out. “And don’t say it’s amazing.”

Probably the last “happening” in Melbourne, it shouldn’t be missed for its utter madness. (Closes 10 December, United Artists Gallery, 42 Fitzroy Street, St Kilda)

_______________________________

Roslyn Oxley9 Sydney 1982

Bilu makes a virtue of bad taste

Susanna Short The Sydney Morning Herald July 8, 1982

From timer immemorial artists have given substance to their dreams of the mysteries of the universe, but it has taken an artist from Melbourne to shape the cosmos with a jigsaw, and nail it down on pieces of plywood,

His name is Asher Bilu, and he is one of the hardest-working artists to be seen in Sydney for years.

His shaped and layered paintings, space-odysseys-in-three-dimensions, make a virtue of bad taste; built up from layers of individually cut, irregularly shaped and fantastically hued pieces of plywood, they success by dint of sheer excess.

At Roslyn Oxley’s the largest work alone would cover the floor space of the gallery if it were laid – or spilt – out.

Called Spillout, and assembled like a jigsaw puzzle that has been capsized, it took the artist two years to make: one to plan, the other to build and compress.

Not surprisingly, it is a decade since Asher Bilu was last seen in Sydney with his work.

Now 30 paintings from 1971 to the present, form a broad survey of the artist’s output. It is a survey that is distinguished by a remarkable degree of industry, if nothing else.

There is something of the naïve builder in Asher Bilu, and artist who is self-taught, and neither entirely figurative not entirely abstract.

Like the French rural postman Ferdinand Cheval, who made the building of his Palais Ideal a life-timer’s work, Bilu allows his paintings to grow by sheer accumulation, and his vision of the impalpable can be as graspable as a square of lino, or pegboard.

But instead of urban junk, it is past styles in art and architecture that are the grist to his artistic mill.

Far from being unsophisticated, Bilu’s paintings are beaux-arts in their effect, as the artist undertakes the reapplication of historical styles, from the Arabesque to the Grotesque, with as much gusto as the carpentry itself.

One has only to look at his pre-Dawning to see a fleur-de-lis edge, The Dream to see an Art Deco medley (curling fronds, powerful dynamos, the rising sun, rippling waves), and Soundscape to see cubism’s chords: cogs, guitars, and wheels-within-wheels. Islamic architecture once surrounded, ands till fascinates, the Israeli-born artist who came to Australia when he was 21 years old.

“The magic of light is all” he says, and there are no shadows in his paintings apart from those formed by the natural penetration of light.

Indeed, in the best of his cosmic paintings, it is light that imparts a sense of the immaterial or floating unreality, as it penetrates the ornamental fretwork.

Three two-dimensional paintings, in shades of black, grey, and bright yellow, work on a different level, however.

While The Journey is an impressive black painting curved like the interior of a giant sphere, and etched with silver – an echo of trailing stars on a cosmic chart Continuum takes the eye from the celestial to the terrestrial, with a surface as pock-marked as the earth’s crust.

It is left to Nothing is Lost to smooth things over with a surface of shiny enamel in the style of famille jaune.

Everything is lost entirely, however, in a roomful of recent paintings in which both the surface, and what is behind it, appears to liquefy before out eyes.

Taking his cue from the Grotesque, a fanciful type of decoration which came to light during the Renaissance, Bilu echoes fairy grottoes as much as anything else.

Times review

The National Times July 18 – 24 1982

Asher Bilu: Great art or pretentious nonsense? At $20,000 a painting one has to be sure. Bilu has worked obsessively with fretsaw and blowtorch to produce these things which may divide gallery-goers into two groups – those who will be delirious with adoration and those who will fall about with mirth. Roslyn Oxley Gallery until July 24.

Bilu: big, bold, brassy and baroque

Arthur McIntyre The Age Tuesday 10 August 1982

SYDNEY. – Undoubtedly the most controversial exhibition in Sydney’s commercial galleries in recent weeks has been that of the Melbourne-based, Israeli-born artist Asher Bilu. His overwhelming creations, some literally cascading from the walls on to the floors of the Roslyn Oxley galleries in Paddington, have defied easy classification. Both critics and laymen have found themselves disconcerted and disorientated.

In terms of overstatement and questionable art-world melodramatics, Bilu’s exhibition is reminiscent of the bad old days of Hollywood when Cecil B. de Mille’s dictum “If you’ve got it – flash it!” was all that mattered at the box office.

Bilu is the consummate showman: maker of big, bold, brassy paintings which are breathtakingly and brazenly 20th century baroque.

So what! Good taste and understatement have seldom made for great art.

Tales of the Cosmos

Sandra McGrath The Weekend Australian July 10-11 1982

I have never seen anything quite like it.

Asher Bilu’s work on view at the Oxley Gallery, Sydney, defies analogies and comparisons. It’s obsessive, compelling, eyeboggling, if you like.

The impact of the larger works, spilling onto the floor and covering whole walls, is overwhelming – confronting the viewer in the manner of a grand opera or a splendid thunderstorm.

How did he do it technically? That question still persists even after close examination of the works. It really doesn’t help to know that one painting’s crusted, fossilised surface was created by blowtorching, and that in others small structural supports have been used to stick hundreds of painted wooden or paper jig-saw shapes to create a three-dimensional effect.

Bilu is attempting to make an heroic visual equation between himself, God and the Universe. Or so it appears.

But what kind of vision is it? One could easily come to the conclusion that Bilu sees Goad as the supreme Jig-Sawist – the Gamesman – the only One who knows how the pieces fit together in a universe of swirling atoms, singing planets, glittering galaxies, mysterious black holes and in fathomed seas.

The curious thing is that despite the multiplicity of jug-saw shapes – the obsessive repetition of them creates a surface order with a logical order of its own.

A whole group of smaller works hang like three-dimensional Chinese scrolls on which rich glazes drip from stalactite forms attached to the background by spidery strands of paint that disappear into a dense interior.

Words tend to make the works seem more visually confusing than they are in reality. Nevertheless it would be wrong not to mention the two summarising works in the exhibition – The Dream and Spillout. Here Bilu brings out all his technical mastery and creates two confounding works that jump out at the viewer like an onrushing train. Spillout seems literally to try to engulf the spectator as it cascades to the floor in great heaps of jig-saw shapes and invades the gallery space in an almost threatening manner.

By contrast The Dream, while still using the same plywood cut outs, suggests not a dream but a pyrotechnic display of ornamentation – rather like a convolute Indian mosaic.

Asher Bilu, born in Tel Aviv in 1936, left Israel in 1957 (sic) and moved to Melbourne where he lives now. Not a well known artist to Sydneyites he had his last exhibition here some 12 years ago at Bonython Gallery. How much being Jewish has to do with the conceptual nature of his work is an interesting question. There have been few famous Jewish painters (Chagall and Modigliani are the exceptions) which is usually explained by the fact that Orthodox Judaism forbids the making of graven images. It seems that Bilu’s themes are somehow deeply rooted in his religion, and that his manner of attacking them, which is closely connected with musical and scientific processes, is in the Jewish intellectual tradition.

He makes the analogy himself : “The creative artist and the creative scientist are one and the same. One technique leads to another. A true scientist tries to disprove his own theories. A true artist does the same. Imagine the music of the spheres with each planet rotating on its axis making a sound. It’s a real thing and an abstract thing at the same time.”

It must be said that not all Bilu’s paintings work. At times the technique dominates and the sensibility is lost. We are no longer in the realm of the music of the spheres but a rather gluggy world reminiscent of the old Ghost Train ride at Luna Park.

But, all in all, Bilu’s show is a must. You certainly won’t see anything like it again in the near future.

_______________________________

United Artists Gallery Melbourne 1983

Memory Holloway The Age Thursday 27 October 1983

Asher Bilu has a strong sense of the theatrical, a marked talent which comes through in the way that his “Arch (sic) and Scrolls” are exhibited at United Artists. There are four small wall hangings and two enormous (well what are they?) drawings hung over frames to loo like celestial gowns. It’s like entering the plastics section of a costume museum.

I much prefer his mad labyrinth of last year, with fans clearing out the hot air and an appropriate soundtrack of electronic music. This show is staid by comparison.

(Closes 4 November, United Artists, 42 Fitzroy Street, St Kilda)

_______________________________

Coventry Gallery, Sydney 1983

ARCS & SCROLLS

Bilu reverses the art-making process

Susanna Short The Sydney Morning Herald Thursday November 10 1983

Asher Bilu is a Melbourne artist whose work has a sense of style not often encountered in Sydney painters.

Last year, he exhibited a series of dramatic shaped and layered paintings, built up from hundreds of pieces of plywood, that spilt from the wall onto to the floor of the Roslyn Oxley Gallery.

Now he is showing eight new paintings whose weight, size, presence, and look of absolute luxury, lift them above the kind of work that is no more than a product of the art-making process.

Indeed, at the Chandler Coventry Gallery, Bilu reverses the very process by which art is made, by turning mundane, industrially produced materials into rarefied art objects that are a cross between soft sculpture and free-standing paintings.

His Arc 1 and Arc 11, in particular, have the look of expensive merchandise and sumptuous drapery, despite being made from spun Plastol and produced by the metre instead of according to the canvas.

While Arc 1, a deep celestial blue, could be a lustrous curtain of the night, Arc 11, pearly in colour, could represent the dawning.

In these extended works, which are made from pouring layers of paint on to a tiled floor, Bilu elevates the ordinary into something extraordinary, in order to give his dreams of the cosmos a tangible – not to say – plastic shape.

Space-aged without being spaced out

Sandra McGrath The Weekend Australian magazine Nov 12-13 1983

It is true Sydney is one of the grandest and most sophisticated cities in the world. It is also a fact that the general quality of art exhibitions in this city would shame a medium size mid-western American town.

While this thought isn’t new to me, it seems to have more bite at this time of the year. That’s not to say there aren’t hundreds of galleries, and on occasion, some very good exhibitions by Sydney artists (we rarely see Melbourne work).

What I am noting is there is an astonishingly small amount of art on an international level to be seen. Only two exhibitions stand out in my memory in two years, both held at the Art Gallery of NSW.

The first was a Kandinsky show held in may 1982, and the other was the brilliant Artist as Illustrator from New York’s Museum of Modern Art, seen in July and August this year.

This really does seem a deplorable situation. What has happened to government sponsorship?

On the local scene the summer malaise (last-exhibition-of-the-year time) is beginning to set in.

But thanks to Israeli-born artist Asher Bilu, a Melbourne resident, the galleries’ season is ending in a marvellous spectacle at Coventry Gallery.

Bilu’s monumental draperies of paint, which he appropriately says are like God’s handkerchiefs, are so unusual they require some explanation.

Nine years ago Bilu was asked to paint a glider for the film The Great Mccarthy with a paint that could be removed easily without damaging the delicate surface of the glider.

He used Plastol, a water-based enamel paint which after drying can be peeled from any surface.

The paint worked perfectly, but Bilu went onto other things, filing Plastol away in his head until last year. After the founding of the co-operative, United Artists, Bilu became inspired to do a large non-commercial “peoples” work.

The result was Amaze, a 43m long, 3m high maze which did indeed amaze.

Amaze is now rolled up in Bilu’s garage waiting for requests from regional galleries to display it. He wants no money for himself, not does he want to sell it.

“It’s such a great introduction for kids to modern art. And isn’t the whole idea to get people into galleries?” he says.

It might also be noted that no Melbourne curators went to see Bilu’s maze. The maze gave Bilu an intimate working knowledge of the material and he decided to create individual pieces with the paint.

These are now on view at Coventry. What is exciting is the manner in which Plastol takes on so many “presences”. Arc 1 and Arc 11, the largest works have been painted on a factory floor, peeled from the floor, and draped over curving aluminium frames. Arc 1 is a fantasy of brilliant blues in swirling circles of gossamer-like webs. With the light shining through it.

Arc 11, a white and black, almost Pollock-like inspiration (remember he dripped and splashed on the floor as well) is alike a white lacy mountain, which another work, Googol, resembles gaily painted organ pipes.

In a technological age, it is not surprising to find material which has so many properties. What is unusual is the technological aspect has not buried the artist’s imagination. Most artists who use space-age materials usually end up spaced out.

_______________________________

Coventry Gallery Sydney 1984

AMAZE

Come into my picture, says artist Bilu

Sandra Mcgrath The Australian Wednesday April 18 1984

What is 42m long, 3m high and composed of one tonne of paint? The answer is Amaze – the work of Israeli-born Melbourne artist, Asher Bilu.

Amaze is a walk through a maze of paint. And indeed, it is amazing.

People walking into Sydney’s Coventry Gallery yesterday involuntarily kept saying: “It’s amazing.”

Amaze is probably the largest non-sculptural work in Australia, though it does have sculptural qualities.

A thick net of pure paint hangs on wires from the ceiling without any other structural support. Walking through the canyons of paint one thinks of brilliant bejewelled spider webs or splendidly translucent stained-glass windows.

Mr Bilu, in a spotted Safari shirt, believes anyone coming to the show will have an experience they will never forget.

“I know if I were a kid it would change my outlook on things.” he said.

“It’s an experience. You’re walking through a painting. It shows paint like never before.”

Amaze is not only the product of Bilu’s extraordinarily fertile imagination, but the product of modern paint and music technology as well.

Nine years ago Bilu was asked to paint a glider for the Australian film, The Great McCarthy, with a paint that could be removed without damaging the surface of the plane.

He found Plastol, a water-based enamel acrylic, which after drying van be peeled off from any surface.

Them in 1982, United Artists – and artists co-operative – was founded in Melbourne, and Bilu was asked to do a large non-commercial peoples’ work.

The work was Amaze.