Artlink Magazine December 2000

Doing Business with the Cosmic

Heather Ellyard

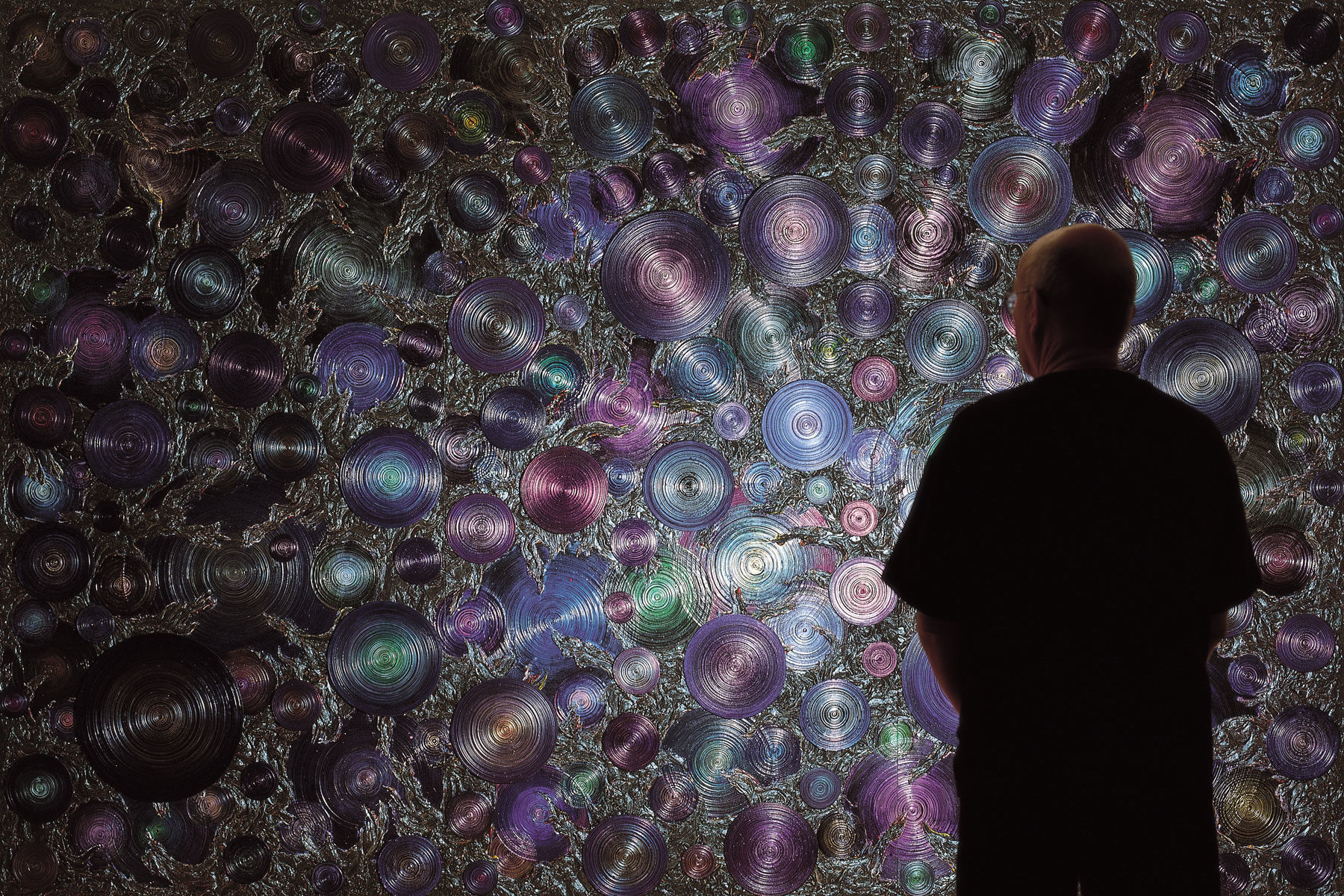

Tam ve-lo nishlam is the Hebrew for ‘finished but not completed’. Hebrew is Asher Bilu’s first language and this phrase is part of the title of his ongoing Infinity Series, begun in 1998. It is an apt entry into Bilu’s attitude to art in general. Making art, for him, is an extended exploration. Call him an inventor. Call his studio a laboratory. Call his process, researching in the fabrication-zone. Call the results, when they succeed, unique and amazing. People ask: how did he do that? Sometimes he asks himself the same question, not having recorded his discoveries in words. He remembers by doing. Always on the alert. Always taking off from the last painting. “I always go back to where I stopped.” he says, pushing everything forward to the next technical limit.

I don’t know of any other contemporary artist in Australia who uses raw material so passionately and transformatively. Asher Bilu steeps himself in matter. He dreams there. Sometimes it’s tons of paint which he mixes himself or paper off-cuts he finds by chance in factory bins or mountains of wood-slivers the size of matchsticks. He works on a huge scale, shaping, pulling, stretching, building, connecting materials not found in art supply shops, not intended for art-making, with consummate curiosity and energy. When he discovered by accident that certain resinous paints, manipulated and allowed to congeal, could be peeled into nets of pigment, he invented lucid skins of colour which later became totally self supporting paintings or “sculptures made of paint”. They are remarkable transparencies in space, alive with gestures of automatic writing and layered implications of light. They took ten years of experimentation to realize. “Nothing comes from nothing.” he says. And means it.

Ultimately, however, all his hands-on speechless working is for another purpose: to turn matter into energy. To move from the rough to the sublime. To distill the plastic reality and take it beyond itself: more inward…more outward. To gaze with metaphysical wanderlust towards the unknown and unknowable, looking for glimpses of consciousness to pin down and rejoice in. I imagine him standing in his work-station, a mature artist, getting ready to do business with the cosmic….using everything he’s got: his body, his music, his yoga discipline, his awe, his eagerness, his practical skills to come as near as he humanly can to the vastness of earth and sky. To record a reverent appreciation. A humble thank you. He calls this the Mystery of the Known, actually the title for one of his Infinity Series. And maybe a small, open-ended commentary on what the known might mean.

From the beginning, Asher Bilu’s work has had two loci of concentration: the mystery of matter, its structures, boundaries and possibilities, and Mystery itself, space, sound, reverberations of the invisible, the very universe. His abiding personal insight is that, for him, one leads into the other. They are not in conflict. Matter is not the antagonist; it is his tool or path for reaching spirit. That breakthrough came early via Paul Klee. Finding Klee’s work and writings, especially the Pedagogical Sketchbook, during his formative years was pivotal. Klee’s teachings released his imagination and opened the access-door to an emphasis on explorations of material. Bilu began a life long commitment to the “endless possible variations” that matter itself offered. As sinew and source.

This persistent and rigorous technical investigation could have been enough. An end in itself. An exuberant lust. His life’s large work. But there is a premise, possibly even a Judaic inheritance, which says that the way to the sublime is through the physical and not through overcoming it. Bilu takes on the physical demands of his experiments like a workman, he manipulates them like a technician, he applies his discoveries rhythmically, like the musician he is (for more than twenty years he has played the Indian 25 stringed sarod and still calls himself a student). Then he watches keenly, patiently for the emergence of larger meanings. And they come. These micro and macro connections. These slants of cosmic light. These minutiae of organic wonder. These soul-openings. They come in exquisite abstract detail.

Patience is a big word. If we attach it to Asher Bilu’s research, to his physical and mental stamina, then we must also apply it to his measure of success. Public success and recognition came early to Bilu. He was born in Israel in 1936, spent his youth on a kibbutz there and migrated in 1956 to Australia. By 1965 he had won the prestigious Blake Prize for religious art (the only Jew to do so) and then, in 1970, he won the national Leasing Prize, judged by the Directors of the Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne state galleries. The Leasing Prize, which called for three submitted works, was non-acquisitive so Bilu was able to take back his entries. He destroyed one and completely reworked the other two. He considered it an opportunity to “take the work further” (again the Hebraic refrain: tam ve-lo nishlam).

One of those re-worked paintings is Nothing is Lost, a very large and dense work teeming with morphic movement held in but not down by geometric angles and reference points. It is an early indicator of Bilu’s combined love of music and art: rhythm, form and colour saturating each other in an abstract polyphony that already wants to leave the flat surface and enter the 3-dimensional zone of his later ‘paintings’. Already it wants to grow towards something else, apprehended but not yet invented.

Asher Bilu’s work sometimes has a long incubation during which time he is constantly testing and developing his technical tools. It seems an alchemical wait. And it seems much more important to Bilu than any external praise. Every artist wants affirmation. Bilu is no exception, but for him real success means to “take the work as far as it and I can go”. He has lived through times when absolutely remarkable work went unremarked upon, in any serious way, such as his marvelous Escape installation at Luba Bilu Gallery during the 1992 Melbourne International Festival. He took 16 tons of those found paper off-cuts, applied florescent paint, used ultra-violet lighting in situ, added his own music, and created a ten day interactive experience which brought joy and lightness of being to seven thousand visitors, young and middling, who were fortunate enough roll about in the shifting crannies and peaks of paper. I was one of them. For me, it was like curling up in a snow dream from my youth in America. A kind of paper-warm violet bliss.

Two years later in 1994 he created another extraordinary installation which filled the main Luba Bilu Gallery shortly before it closed. This time the sculpture was ineffably still, except for the air-waves made by viewers walking near the thirty metre long spine-of-rope and setting it in slow motion. The rope was slung in a resinous connecting curve between two soaring towers and became a kinetic life-line between them. The work was called Sanctum, and being there in the white silence of the towers, constructed somehow from thousands of those wood slivers, was to be in a place of ascension. The towers were diagonally situated at opposite ends of the gallery. The suspended coloured resin-rope was a sensate conduit between them. They stood separate, equal and in the kind of magnetic attraction that inspires grace. Around them, the gallery walls were studded with hundreds of small wood scraps, painted white, transformed into mnemonic shards from a forest of white dignity. This show, breathtaking technically and spiritually, came and went un-reviewed. But not un-remembered. Subsequently, the towers, nudged a little more, were exhibited in World Without End, a brave, inaugural group show at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne, in 1997. Also un-reviewed.

When the structure of matter is taken to its sublime contemplation, it enters a place of cosmic speculation. Understandably, sublime intentions, if they are noticed at all, move in and out of currency in a marketplace not known to hang out in the spirit-zone for very long. It requires daring to notice. And curatorial courage to shine the light on such art. But that passionate interface between the human and the eternal is where Asher Bilu takes his work, regardless. More and more so with each new process and each new strategic realization.

His most recent work, the Infinity Series, grew out of a major commission proposal which never eventuated. Bilu had made a dazzling sculptural maquette, life size but minuscule compared to the vision he fully intended. Thousands of small balls were painted gold and strung together like beaded nanos of the universe. They were suspended in particle-clusters of various lengths from the ceiling. Every stirring of air moved them. Light moved them. Even looking at them, with the eye’s energy, seemed to move them. One has to be careful with gold. Too much can cause an overload of glitz and a psychic short-circuit. Asher Bilu’s Infinity had too much gold, but not for its intentions, which were infinite. Being under it, looking up, felt like being among stars, mesmerized towards carbon-remembered luminosities.

From that gold-expansion he returned to some ‘unfinished’ business. In the late 60s, Bilu had made paintings of abstract graphite spheres, literally dense with carbon-layers. A gut feeling took him back there, with both Infinity and improved techniques on his mind. The result was a huge, austere Black painting, honed, simultaneously condensed and expanded, as though matter itself were being turned into movement and space while remaining wholly still. With the simplest tools and the most disciplined rhythms, this work manages to contemplate the Awesome truths of darkness and light. It lets you cry.

Asher Bilu kept looking at this painting for a year. Looking led to further developments. The single painting grew into a series: Metallic Green, Red, White, Gold. In the end he went back to the beginning and restlessly re-worked Black, making it better. He says, “If I had sold that first black painting during that year, it would have been gone but unfinished…” He adds, “Sometimes it pays not to be too successful…it can lead to loss of reference.”

For Asher Bilu, the only way to go about being an artist is to say something that hasn’t been said before. “It’s humbling, but I’ll give it a bash.” he says in his adopted vernacular. And I am reminded of an eloquent quote by George Steiner, a fellow Jew, who wrote:

“All understanding falls short. It is as if the poem, the painting, the sonata, drew around itself a last circle, a space for inviolate autonomy.”

Maybe this is the success that Asher Bilu, the dreamer-technician, reaches for with a sure hand, a steady eye and an immense love of life.

Heather Ellyard is an American born Australian artist living and working in Melbourne.